Former President of Ireland, Mary Robinson, when asked to speak on the proposed divorce referendum in 1986, said: “I would have reservations about the restrictive nature of the proposed referendum […] Divorce, in fact, is not so much about marriage breakdown. It really is about the right to re-marry. I think we are trapping people cruelly and unnecessarily.”

Thirty years later and Robinson’s premonitions have proven prophetic with great public demand for a loosening of the constitutional conditions surrounding divorce in Ireland. Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Josepha Madigan, made the original proposal to amend Article 41.3.2° so that couples, in order to be granted a divorce, will only be required to live apart for two years instead of the current four. The government has now gone a step further and proposed a complete removal of the time period from the constitution, allowing it to be dealt with under statute. “The government has now gone a step further and has proposed a complete removal of the time period from the constitution, allowing it to be dealt with under statute.”

The referendum is set to take place on Friday May 24, the same day as the local and European elections. Yet, this “appetite” for change, as Madigan has publically phrased it, is all despite Ireland boasting the lowest divorce rates in Europe according to the EU’s statistical arm, Eurostat. But is this necessarily something to boast about?

Ireland’s low rate of divorce has been attributed to factors such as people marrying later in life and high levels of education. However, the onerous conditions surrounding divorce undoubtedly play a key role, with Irish couples opting to remain legally separated rather than suffer the painful process of getting a divorce. The former option of legal separation only requires that couples live apart for one year, in contrast to the latter option of divorce which stipulates four years. Divorce also requires that couples satisfy other conditions, namely ensuring financial provision for a spouse and dependent children.

The key difference between separation and divorce: separation does not allow either spouse to re-marry, whereas divorce does. Hence, the introduction of divorce into Ireland, where separation was previously the only available option, brought with it a right to re-marry.

Margaret Weymes, a psychotherapist in FT Counselling Centre, speaking to Trinity News about the difficulties of the four year time requirement, said: “I think it hurts people, basically the time period is too long. The marriage may have been in a lot of difficulty for a long time and – because they are not able to move on physically, dividing up property etc., until the divorce has been granted – it can extend the inevitable and prove damaging in the long run.”

Article 41.3.2° seems to present a dilemma in that, on the one hand, it confers a right to re-marry, but at the same time it also makes it very difficult to access this right. This is no doubt due to the historical concerns around divorce and the fundamental role marriage plays in the make up of society.

Professor Gerry Whyte, a lecturer in Trinity’s Law School, speaking to Trinity News, acknowledged how “this proposed referendum, if passed, will make it somewhat easier to exercise the right to re-marry”. The plan to delete the four year time requirement and deal with divorce exclusively under statute instead allows ministers to debate and prescribe more detailed provisions under which a divorce can be granted by the courts.

“Professor Gerry Whyte, a lecturer in Trinity’s Law School, speaking to Trinity News, acknowledged how ‘this proposed referendum, if passed, will make it somewhat easier to exercise the right to re-marry’.”

The question is: why does Ireland, a country with an increasingly liberal consensus, have such conservative restrictions imposed on the dissolution of marriage? This conservatism seems especially anachronistic in light of the 2015 same-sex marriage referendum in which an overwhelming 62.07% of Irish voters voted yes to same-sex marriage. In order to answer this question, the history of divorce in Ireland must be examined.

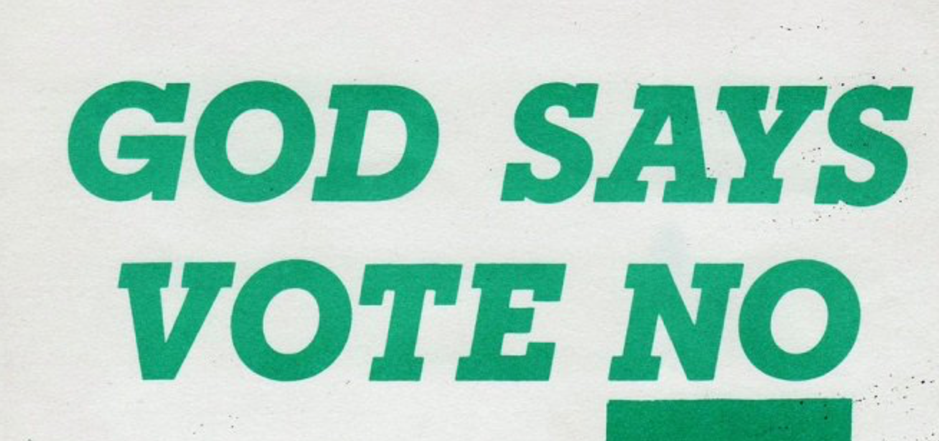

“Divorce Kills Love: Vote No” was a slogan echoed throughout the lead up to the first divorce referendum in 1986. The No campaigners ultimately dominated the polls, winning 935,843 votes to 538,279, in what was an overwhelming rejection of the introduction of divorce to the Irish Constitution.

Denying the recognition of a right – in this instance the right to re-marry – may seem peculiar today when the importance of personal rights occupy a considerable segment of public dialogue. However, it must be remembered that the Ireland of 1986 wore a totally different face to the Ireland of 2019. This was when The Troubles were at their nadir. The Newry mortar attack, a catastrophic bombing that claimed nine lives, occurred only a couple of months before the initial referendum campaigns began. In the background of this, the Republic was further trying to distinguish itself from Britain in any way it could, mainly through strict adherence to Roman Catholic social teachings, a doctrine which strictly prohibits divorce.

In 1986, homosexuality was still a punishable offence. Moreover, marital rape was legal and would remain so until 1990. Clearly, egalitarianism and alternative views of marriage were not at the forefront of the Irish conscience, but rather a devout loyalty to the ideal “traditional family”.

Ten years later and the residue of this ultra-Irish Catholic conservatism was still very much present. In fact, in many ways it was amplified as conservatives and the church realised that this referendum would be far more closely-fought than the previous, with Ireland at the cusp of what David McWilliams, adjunct assistant professor at Trinity, calls “Dún Laoghaire-isation,” a societal shift to liberalism.

Due to this greater competition, the 1995 divorce referendum suffered from increased division and fearmongering. An infamous placard reading “Hello Divorce… Goodbye Daddy…” epitomised the concerns that the introduction of divorce to Ireland would completely undermine the institution of marriage. Alongside sensational platitudes, the No campaigners also made an example out of the UK; that year England and Wales recorded over 150,000 divorces, according to the Office for National Statistics. Many feared that, by introducing divorce, figures would begin to skyrocket.

It was in order to appease these concerns, and many others, that the drafters of the 1995 constitutional bill enveloped divorce in multiple burdensome conditions, enshrining a constitutional right to re-marry but at the same time making it difficult to achieve in practice.

These concessions, now matched with a slightly more liberal electorate, would prove just sufficient enough for the bill to pass and for the ban on divorce in Ireland to be lifted. The Yes votes passing by the narrowest of margins at 818,842 votes to 809,728; less than 10,000 votes separating the sides.

The aftermath of this historic moment saw a different Ireland raise its head, one that had grown significantly since 1986. John Bowman, a broadcaster for RTÉ, closed the referendum broadcast with “the new history is that Ireland has voted for divorce. It’s perhaps a case of hello divorce, goodbye de Valera”.

““Trapping people cruelly and unnecessarily” cannot and does not reflect the modern Ireland – where acceptance and autonomy are given privilege over all else.”

In retrospect, Bowman’s forecasting of Ireland slowly extricating itself from the clinch of conservative Roman Catholic teaching seems well placed. Since then, we have seen the people of Ireland resoundingly vote yes to same-sex marriage, abortion, and the decriminalisation of blasphemy; three taboos that in 1986 would be considered cardinal sins, but that have subsequently become increasingly acceptable in the eyes of the Irish public. By and large, what was once considered reproach-worthy taboo have now become completely accepted and, in the case of same-sex marriage, celebrated.

Can a landslide victory for easier access to the right to re-marry be extrapolated from the resounding support for the above constitutional amendments? We’ll know in May, but what can be said is that, over the last thirty years, Ireland has undergone an economic, political, and legal renaissance. Thus, the symbolic nature of the referendum cannot be understated, with divorce still being subjected to strong stigmatisation. A 2015 survey by separated.ie showed that almost half of Irish people who have been separated or divorced feel that they still face a substantial level of stigma.

This referendum, if it passes, would symbolise a mature public acceptance of reality: relationships break down and marriages fail. It is not always a fault-based separation. It is not something that deserves condemnation and it seems high time to eschew the residual taboo. “Trapping people cruelly and unnecessarily” cannot and does not reflect the modern Ireland – where acceptance and autonomy are given privilege over all else.