At the beginning of September, work began on the Trinity Colonial Legacies project, first announced in February of this year, when Dr Mobeen Hussain was appointed postdoctoral research fellow to the project. Led by Dr Ciaran O’Neill and Dr Patrick Walsh of College’s history department, the two-year research project will examine how the college has variously facilitated and benefitted from the exploitative and often brutal imperialism of the global British Empire. Speaking to Trinity News, Dr Walsh outlined that with the project in its most preliminary stages, it is important to take a broad, unprejudiced approach to the research: “We are currently keeping our focus quite broad with an intention to consider Trinity’s colonial legacies in the round ranging from financial legacies to collections, to the memorialisation of individuals, to College’s connections to different societies across the globe as well as its historic connections to communities in Ireland.”

Ireland’s place in the history of colonialism is unique and multifaceted. Ireland was the first colony of the British empire, and was exploited for its land and resources for centuries. However, it has also played its part in the colonization of the rest of the world, and many Irishmen upheld colonial interests overseas. Acknowledging the very broad scope of the subject, Dr Walsh said: “There is much to investigate and it is hard to prejudge what we will find, and you must remember this is primarily a research project.” As is important in academia, the primary goal of the project is to research and document, before making unfounded assumptions or inadequate conclusions about the past.

Colonisation of Ireland

There is much that we already know about this aspect of the College’s past, however. The college’s very origins are rooted in the plantations of Ireland and the expropriation of land. The site of the college had formerly housed the Augustinian Priory of All Hallows until its suspension in 1538 under Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries during the Reformation. Half a century later, the college was founded bearing the name of his daughter, Queen Elizabeth I, which it still bears today. This reappropriation of land was typical of English colonial practices across Ireland.

The college’s foundation at the end of the sixteenth century was no coincidence. The college was founded to provide university education, rivalling that of Oxford and Cambridge, to young men of the Protestant Ascendancy, Ireland’s political elite following the plantations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Between the 1550s and 1620s, Catholic land ownership fell from 60% of land in Ireland, to less than 10%, transferred into the hands of British settlers. The foundation of Trinity College in 1592, right in the middle of this process, was due to the rapidly increasing number of settlers arriving in Ireland creating demand for an academic institution in Ireland. Trinity therefore owes its very existence to an unjust and violent regime of settler colonialism.

The College itself benefited greatly from the confiscation of land in Ireland. A Royal Commission of 1905 found that Trinity’s estates totalled around 200,000 acres across sixteen counties in Ireland, much of this dating back to the time of the plantations. The bulk of this lay in Kerry and Donegal, with significant holdings also in Armagh, Fermanagh and Longford. The complex system of letting and subletting in place at the time exploited the poorest inhabitants of the country in order to benefit landlords, Trinity itself among them, collecting revenue for land that was taken by force in the first place. This exploitative legacy is one of many the College must reckon with.

“Beyond just its links to problematic individuals, however, the college itself as an institution has ties to the transatlantic slave trade.”

Global British empire

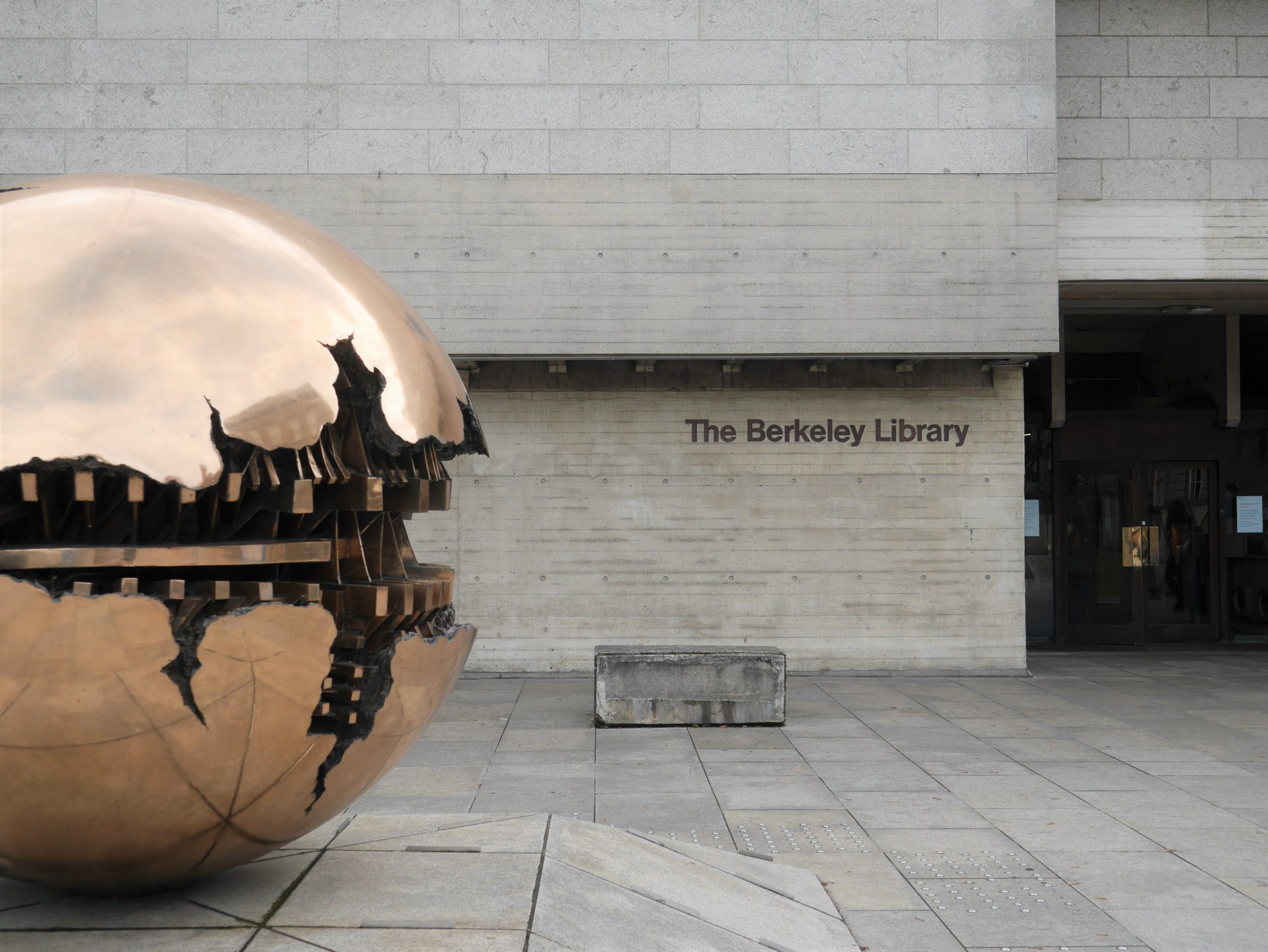

It is not just Trinity’s place in the history of Ireland that has been questionable. Recent discussions have highlighted prominent individuals in the college’s history with alarming links to colonialism; one such figure is philosopher and fellow of the college George Berkeley, after whom a college library is named, who himself owned a number of slaves. John Mitchel, an Irish Nationalist figure who supported and defended the practice of slavery as late as the latter half of the nineteenth century was also a graduate of the college. Beyond just its links to problematic individuals, however, the college itself as an institution has ties to the transatlantic slave trade; both the Irish Times and the Guardian have reported on the fact that Trinity’s main entrance on College Green was financed by a duty on tobacco, a crop primarily cultivated and harvested by slaves. The stolen labour of unpaid workers on the North American continent indirectly built the gates through which students, staff and visitors continue to pass today. This aspect of the college’s past is something that is under-emphasised in the study of its history up to now, and there is much we still do not know, something which the Colonial Legacies project aims to rectify.

“Trinity also played an important part in the machinery of the British empire long after slavery was abolished.”

Trinity also played an important part in the machinery of the British empire long after slavery was abolished, facilitating the expansion and maintenance of imperial institutions in Britain’s colonies all the way into the twentieth century. As Dr Tomás Irish notes in his study of Trinity during the First World War and Irish revolutionary period, the British empire offered wide opportunities for employment to Trinity graduates at the turn of the century, particularly from its professional schools. A professional qualification was “a license to travel”, an opportunity which was eagerly taken up by alumni who took up their profession across Britain’s many colonies. In Dr Irish’s words, “the college was proud to play its part in the imperial project.”

The College also trained students for the Indian Civil Service examinations, exporting its graduates as servants of British rule in India. At this time, the British empire was actively suppressing independence movements in India, often with violent force. The most brutal example occurred in the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre, in which British Army soldiers opened fire on peaceful protestors, killing at least 379 people. This is just a single example of how the British empire was maintained through physical force. Trinity College was complicit in a system upheld by violence and resistant to the will of the people it ruled, India being just one example of Britain’s imperial presence around the globe.

Contemporary colonialism

Importantly, Dr Walsh highlighted that it is too early to say yet what implications the project’s findings might have in terms of College policies going forward. Indeed it is likely that uncovering the truth of the past may raise many questions about the present and the future. Imperialism and colonialism are themselves certainly not phenomena of the past. American imperialism is a regular object of criticism by academics such as Noam Chomsky, while its close ally Israel is the most prominent example of settler colonialism in the world today.

In August of this year, it was revealed that College has €2.5 m invested in the armaments industry. The portfolio included investments of hundreds of thousands in companies Lockheed Martin, Honeywell International and Raytheon Technologies, among others. Trinity News subsequently reported that these companies have been connected to airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition, with which the US is intimately involved, in the ongoing war in Yemen according to research by Bellingcat, the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights, Yemeni Archive and Forensic Architecture.

More troubling still, each of these companies is openly involved in contracts with Israel’s Ministry of Defense. F-35 warplanes, manufactured by Lockheed Martin, were used in the bombardment of Gaza in May this year; in 2012, Honeywell International signed a $735 million deal to supply jet engines to Israel’s Ministry of Defense; Raytheon partly designed the Iron Dome Weapon System which allows Israel to attack populated Palestinian areas without restraint while it heavily defends its own cities. Israel’s confiscation of Palestinian land and settlement of its own people directly mirrors the history of the plantations in Ireland. Investment directly supplied by College’s endowment fund allows the development and manufacturing of these deadly weapons which are used by Israel in the illegal occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. Seemingly, College’s complicity in imperialism and colonialism is not a thing of the past, but continues very much to this day.

As Dr Walsh put it, it is important to complete the research before drawing conclusions about the past. The project is a vitally important step in understanding and acknowledging Trinity’s complicity in colonialism and how it benefited from the injustices of the past. The findings of the project will likely spark entirely new debates and prompt questions about the future; college will inevitably have to reckon with the injustices of the present day if the project is to be presented with integrity. The important and admirable work of academics in investigating Trinity’s history must not be undermined by the College itself profiting from unethical investment and continuing to be complicit in the present day with what it condemns in the past.