As a historic campus at the centre of Dublin city, Trinity College Dublin has witnessed the changes of centuries. College itself has undergone much transformation, though some elements from the past are still recognisable today. Photographs of Trinity, both past and present, provide a glimpse into how campus has evolved over the decades.

Front Square

Since its construction in the 1750s, Trinity’s western façade – known as Front Gate – has been the College’s recognisable ‘face.’ Though the Campanile can be seen as the more iconic symbol of College, plastered on countless pieces of merchandise, Front Gate is the standard backdrop of any visiting tourist’s selfie, arguably making it Trinity’s true emblem and the official threshold between city and campus.

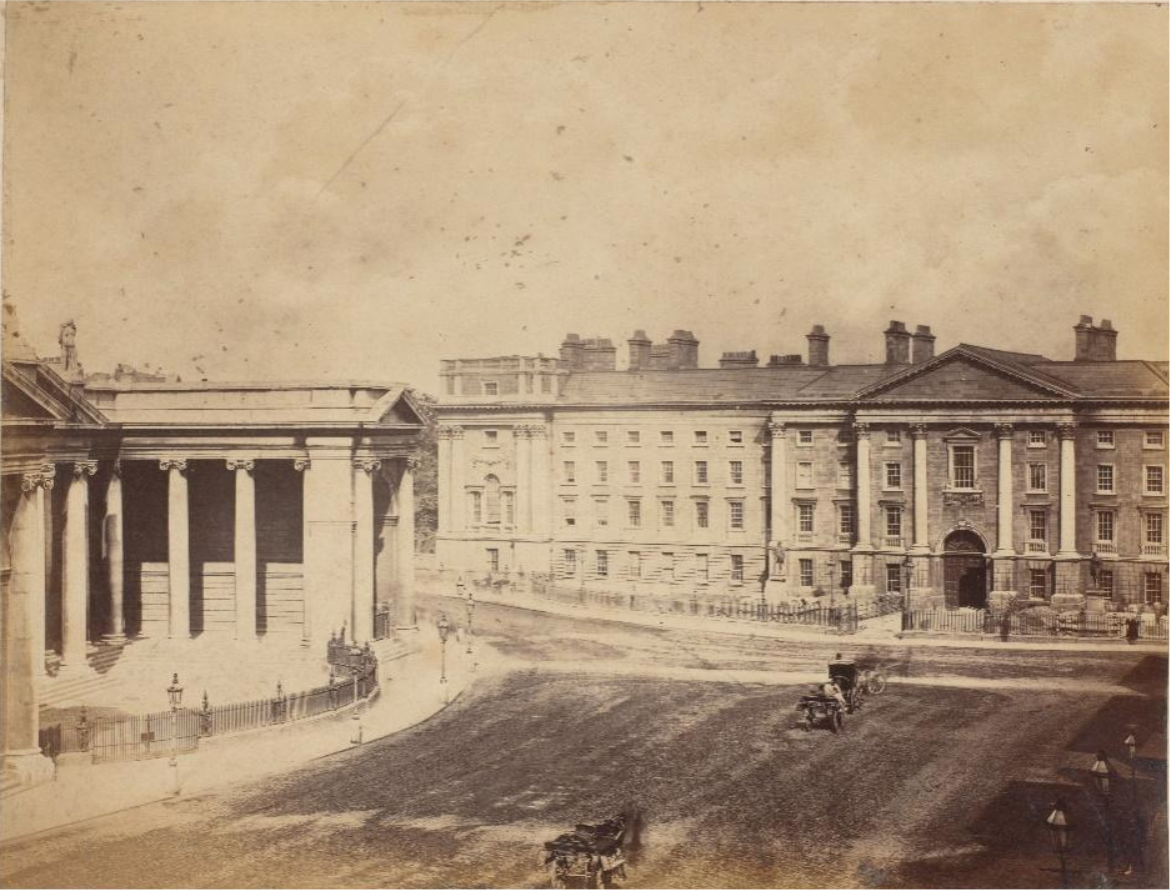

Looking out onto College Green, the granite façade, with its neoclassical design, has remained unchanged as the city has evolved around it. Photographs from various points in Trinity’s history chart this relationship. An early photograph from 1871 (below) shows the wide expanse of College Green between the Bank Of Ireland and Front Gate, occupied only by a few horse-drawn carriages. Taken just one year before Dublin’s tram system was introduced, the cobbled street is yet unmarked by tram lines.

A subsequent photograph from the 1930s, more closely focused on the principal façade, speaks to the rapid changes that occurred in those 50 years, with the tram lines that came to service large areas of Dublin until the 1940s visible in the right-hand side of the frame. The College Green tramline was the first to be laid in 1872, but was removed in the 1940s to pave the way for a more car-centric city centre; one pylon used for the original tram power lines actually still exists in College today, in the Chief Stewards’ Garden.

Tracks along the same route were reinstated in 2004 to service Dublin’s Luas tram system, with Trinity gaining its own stop along the green line in 2017. A snapshot of Dublin’s mid-century revamp towards car-centric design can be seen in photographs of Dublin’s first major pride parade from 1983, where a Ford Fiesta and a Datsun Sunny can be spotted among the marching crowd.

Front Gate today. Photo by Nicholas Evans for Trinity News.

Student Activism

Unsurprisingly, given its central location and ever-growing student body, Trinity College was a hotbed for Student activism throughout the twentieth century. Constructed opposite the former Irish Parliament, now the Bank of Ireland, Trinity’s western façade has been inextricably linked to the social and political development of the city since its erection. College’s pilastered facade became the backdrop for a number of social movements, including Dublin’s first Pride parade, seen below. Amidst the small sea of people who attended the 1983 Pride Parade, a Trinity Student Union banner can be seen, peeking out of the corner of the photo; similarly, in 1992, Trinity students were photographed marching towards the Dáil along Molesworth Street as part of the 1992 anti-eighth amendment protests sparked by the ruling of the controversial ‘X’ case, which forbid a 14-year old rape victim from accessing abortion services in Britain. Though not taken on campus, it does reflect how issues on campus bled out onto the city streets, with change in the city influencing change on campus and vice versa.

Dublin’s first pride march in 1983. Photo courtesy of Daniel Wood Photographic Collection.

Changes within campus:

“In 1983, Trinity’s total enrollment was around 6,000; today, it is approximately 20,000”

While Front Gate has stood as a constant, recognisable structure amidst the ever-changing physical and social fabric of Dublin, campus itself has changed drastically, particularly in recent history. The introduction of free secondary school education in Ireland and the increase in third-level grants, as well as the official removal of the Catholic episcopal ban in 1970, saw the demographics of College shift and the size of the student body increase. In 1983, Trinity’s total enrollment was around 6,000; today, it is approximately 20,000. This increased attendance, paired with the growing numbers of tourists visiting campus every year for their Book of Kells and Normal People fix, has necessitated change.

From the construction of the Arts Block in 1978 to the acquisition of property along its borders with Pearse Street and Westland Row throughout the 1990s, Trinity’s campus has expanded. The construction of Printing House Square is the most recent in this long line of physical changes on campus. When one compares a photograph of today’s Printing House to one of its 1871 counterpart, it becomes evident that little has changed about the original architecture. Only today, the moulded planes of the new complex’s granite roof loom over the original.

The original Printing House, taken circa 1871. Photo courtesy of the TCD Library.

Printing House today. Photo by Rory Chinn for Trinity News.

The physical growth and expansion of College not only necessitated a rethinking of Trinity’s physical size and architecture, but it also meant changing the way people interact with nature on campus, sparked by the growing importance of sustainability. When comparing photos of campus today to those taken in 1983 by David Hackett, Trinity’s now Environmental Services Co-Ordinator and former Head Gardener, these changes become more evident.

Students sitting outside the entrance of the Long Room, 1983. Photo courtesy of Head Gardener David Hackett.

Students sitting outside the entrance of the Long Room today. Photo courtesy of Trinity College Dublin.

When Hackett took these photographs in 1983, he was a student of Horticulture at Trinity’s Botanic Gardens, with no idea that he would later work for the College. Since 1993, however, Hackett has been responsible for the maintenance of all 17 of Trinity’s sites, including the primary campus at College Green, Trinity East, Santry Ivy Grounds, and the grounds at Tallaght and St James’ Hospitals.

Speaking with Trinity News, Hackett recalled the changes he has witnessed during his time working for Trinity: “there’s been an increase in students, yes [and] tourists, but also buildings and developments which have had an impact [on campus].” A comparison between Hackett’s shot of the Old Library and Fellow’s Square and its contemporary counterpart clearly shows the rise in numbers on campus, both visiting and students.

In 2017, the long-established ban on walking on the grass at Fellow’s Square was lifted, described as “impractical” and “impossible to enforce” by Estates and Facilities. This policy shift has seen tourists and students alike populating the green space, often to the detriment of the grass, as visible in the most recent photograph.

Walkway along route to ‘the Pav’, 1983. Photo courtesy of David Hackett.

Photo courtesy of Trinity College Dublin

Curating campus’s green spaces to handle human traffic requires care and attention. Hackett cites continual intervention as key to allowing both College and its trees to grow and flourish. Evidence of this success can be seen in Hackett’s photos too, in which the wild cherry trees, visible as saplings in protective wire mesh in 1983, are pictured in their maturation in the recent photograph of students walking along College Park. With the lifespan of certain trees on campus projecting hundreds of years into the future, Hackett reiterates the importance of long-term planning.

According to Hackett, College’s physical maintenance has always and must continue to abide by two major rules: “it’s important to maintain its character, but also to ensure it is future ready.”