For me, Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon represents more than just “music”; it is Burke’s subliminal incarnate – only in musical form. Undoubtedly borne out of the daring experimentalist leap produced by the Beatles in their Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, their two-month-long recording stint at London’s very own EMI (now “Abbey Road”) proved to result in something hitherto unheard. For many, this album is unquestionably the greatest show of musical genius ever produced by man; for others, a close second. But what exactly makes the album so special?

Instrumental Innovations

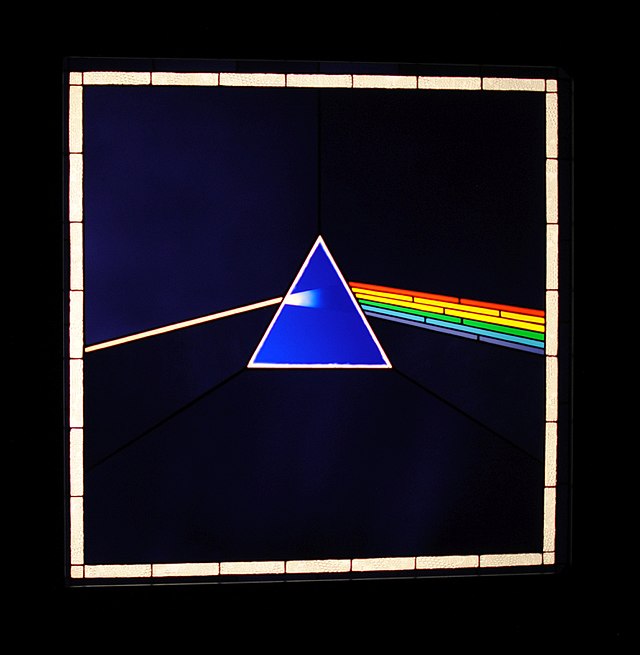

Recorded at different intervals between 1972—1973 at EMI’s (now Abbey Lane) studios “2” and “3”, the album was intended as, according to Roger Waters, an expression of “political, philosophical, humanitarian empathy that was desperate to get out”. Though most extol it for its lyrical virtue, and would extend its scientific roots simply to the cover’s representation of light refraction, the science and diversity of craft and method behind its production is – if anything – more intriguing than that contained in the lyrics.

The band had the pleasure of working with Abbey Road and Let It Be’s very own Alan Parsons for the album’s recording. Though equipped with a 16-track recording equipment, they frequently faced problems of over-laying. This left the band, as Parsons recollects, to reduce the tracks down to even or eight, in order to leave more space for overdubs. Though as a downside, the tape lost in quality during mixdown. Money, for example, starts off with an odd 74 loop of coins being thrown into a mixing bowl, partially recorded in Waters’ wife’s gardening shed with his “first proper tape recorded”, and otherwise using tapes available at EMI. (Harris, 2005: 101) Given the album was designed for quadraphonic, the seven sound tapes had to be individually recorded on a one-inch loop. With each sound lasting about a second (that is, 15 inches of tape), that made for 100 metres’-worth of tape. Perhaps more notably, On The Run is entirely founded on the use of an EMS Synthesiser. Though they’d previously used EMS equipment in their recordings of Meddle and Obscured By Clouds, their recording of DSOTM timed perfectly with the release of EMS’ Synthi AKS. Innovatively equipped with a sequencer (a device that puts received pitches into a repeatable pattern), it had three oscillators, each linked to two respective modifier outputs and a shape control to change the symmetry of the output waveform.

It also had amplifier modules with level and pan control, reverb, and diode ladder filters. This latter was built to work around a similar patent, and worked as a voltage-controlled filter, limiting current electrical flow to a filter capacitor, allowing the user to manually change the cutoff frequency. As the story goes, Waters, while playing with the attached sequencer, came up with an eight-note sound pattern for the song, later using the rest of the equipment to instinctively amend the outputted soundwaves. In fact, all the sound effects used in the album come from the machine. To my knowledge, the overture track Speak to Me was also the first opening track of any album to contain crossfaded snippets of the songs that were to follow on the album (the very converse having been done by Genesis to conclude their experimental masterpiece Duke.) Speak to Me is also revolutionary in that it popularised the use of the first commercial noise gate, the Kepex – a device which allows the user to input an audio signal threshold below which none will pass; allowing, principally, the reduction or elimination of unwanted noise. Indeed, the opening heartbeat – reminiscent of a techno bass drum – is essentially, as Alan Parsons put it in a June 1998 interview, “a gated bass drum”.

Though the rest of the songs on the album are similarly inspired, comment may be additionally passed on the use of a Leslie Speaker on Any Colour You Like – apparently inspired from Clapton’s Badge (Povey, 2010:161). The purpose of a Leslie Speaker is ingenious: working on the Doppler effect, the speakers (or horns) are made to rotate around a pivot point in a cabinet. Slow rotation (chorale) gives you a more ambient sound; fast rotation (tremolo) creates a more syncopated, nauseating sound. Both work around frequency modulation as the doppler effect occurs periodically with every speaker spin – the tremolo effect is simply more pronounced as the speed increases. As the soundwaves reflect off nearby surfaces, the constantly shifting reflections cause complex phase-shifting. Phase being a measurement of time expressed in angular degrees, a phase shift is the difference between two different points on a soundwave cycle.

Live Shows

Following the release of Dark Side of the Moon was a series of never-before seen “electric theatres”. This entailed the presence of large, circular screens on stage, together with moving lights supported by cranes and dry ice flowing from the front of the stage onto the audience. Most impressive, however, was the inclusion of a surround sound system. Though dating back to the 1940s with the release of Disney’s Fantasia, Pink Floyd retains the record for first use of surround sound at a live gig. The science behind thus is rather simple – premised around the use of a quadraphonic speaker system (i.e. emitting two sounds from the front and two from the rear), with the audio of each speaker being individually channelled in from what they termed the “Azimuth Coordinator”, they would use four variable resistors (“rheostats”) in this latter to swivel the sound output from one speaker to another – with the output being equal in all speakers. Also used live was a large, circular screen that with time transmogrified into a system displaying screen films and lighting rigs. With time, the screen also became retractable and could display light at various angles. It provided the band with a uniform surrounding that wasn’t dictated by the shape of the building. One need only watch the band’s live performance of Any Colour You Like at Brighton in 1972 to get just the slightest idea of how wholly immersive the experience was.

Concluding…

Uncontrived and universally relatable, the album has yet to go out of style, consistently remaining on numerous national Top 200 Charts, all the while plaguing the rock scene with a sort of Haroldian anxiety of influence. The work is more than just musical genius – it is sonic innovation at its purest, headed by a team of bright, talented, and daring individuals.

Concluding, we may look to the words of Alexander Gerard (1774:26) to get a clearer understanding of why it has remained so enduring:—

“in all the arts, invention has always been regarded as the only criterion of Genius […] We ascribe so great merit to invention, that on account of it, we allow the artist who excels in it, the privilege of transgressing established rules, and would scarce with even the redundancies of his natural force and spirit to be lopt off by culture”.