There are three messages that I remember receiving very clearly during sex ed. classes in secondary school. The first, naturally, was “Don’t have sex.” This was swiftly followed by Condom Application for Beginners, once we got to the age where the cool kids would get in trouble for hanging around the local boys’ school on the morning of Valentine’s Day, and the prospects of us retaining our purity were rapidly diminishing. The third was “Don’t do anal” – that’s not relevant at all, it’s just that I can remember a disproportionate amount of time in these classes devoted to its discussion. Given that I am a product of an incredibly stereotypical all-girls’ Catholic school, this actually seems quite liberal as I look back on it now. I’m quite surprised at the fact that they acknowledged the existence of anal at all.

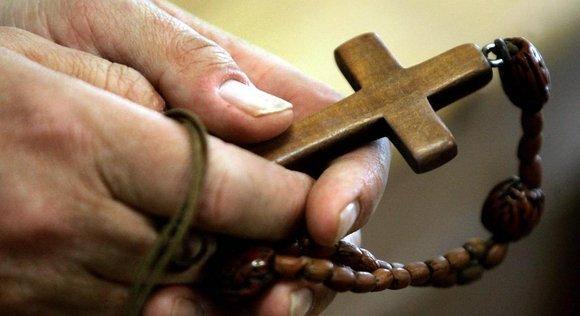

The picture is unsurprisingly similar in a huge number of schools. While sex education is technically mandatory in Irish schools, the Department of Education guidelines allow principals and boards of management to determine what is taught; there is no set curriculum, no minimum standard of topics to be covered. Moreover, it is encouraged that schools keep their sex ed. classes in line with the school’s philosophy and ethos. This is a terrifying prospect when you take into account the fact that over 90% of secondary schools in this country are Catholic schools, meaning that they are based on a conservative Catholic ethos. That ethos has an incredible ability to stunt the delivery of effective, accurate and unbiased sex education.

On the whole, sex education in Ireland gives a profoundly negative view of sex. The predominant messages focus on its negative aspects – unplanned pregnancies, STIs and the ever-popular idea that the more sex you have, the less special it gets. In fact, I once heard of a sex ed. class wherein students were told to pass a piece of sellotape around the group, noticing how it became less sticky – just like sex becomes less special. That is what currently passes as acceptable, government-approved sex education in this country: biased, meaningless metaphors that are completely useless and portray recreational sex as something that you’ll regret for the rest of your life. Any useful information on contraception and STI prevention which is actually accurate (which it often is not) is consistently presented against the backdrop of abstinence being the only 100% effective method of contraception, and therefore the only right answer.

We desperately need to acknowledge the fact that the system is failing to teach students an infinite number of incredibly important things. The emphasis on keeping sex ed. classes within the remit of the sex-averse Catholic ethos necessitates an emphasis on abstinence and “purity”. With this being the foundation of everything, teachers are hugely limited in the material they can realistically cover. If the main objective of the course is to keep us on the straight and narrow road of abstinence, the idea of arming students with the skills and knowledge they need to enjoy their sex life and be fulfilled essentially goes out the window. They can’t teach us to cope well with something they’re pretending we’re not doing in the first place. They can’t enable and empower us to enjoy something that we’re only ever supposed to regret. It is this basis of sex ed. in the Catholic ethos that has seen it develop into nothing more than structured, state-sanctioned scaremongering at the hands of those charged with the development of our students.

In essence, the major change that needs to happen is the introduction of positive attitude towards sex in these classes. Not to the extent where students feel that sex is the be all and end all, but enough to allow them to believe that sex isn’t something dirty that should never be talked about. At the end of the day, the emphasis put on abstinence won’t stop most students from having sex. What it does do though, is perpetuate the stigma that still surrounds it. While attitudes towards sex have become somewhat more progressive in the past few decades, it’s still very much seen as something that shouldn’t be talked about. There are few opportunities whereby we can be totally honest and frank in our discussions about sex, because we live in a culture that tells us not to be. Coming at the age where we’re beginning to mature sexually, sex ed. needs to provide that forum for young adults, so that they can take from it not only practical advice, but also a healthier attitude toward sex and an openness to discussing it.

Imagine a world in which the basis on which sex ed. is taught isn’t one of shame and dissuasion, but one of positivity and embrace. If the ethos of the curriculum became the belief that students should be empowered to lead a healthy, happy, fulfilling sex life, it suddenly becomes possible to provide them with the knowledge to do so. Think of all the useful things we can actually start teaching students: sometimes sex is uncomfortable, here are some reasons why; some people hate using condoms, here are some alternative methods of contraception; if you’re getting bored with your sex life and it’s affecting your relationship, here are some fun things to try. Much more than that though, it encourages much more open dialogue about sex. We need proper, open discussions about what consent is and how to establish it. Students need to be able to address the emotions that often accompany sex – to be aware of them and to be able to deal with them. People need to realise that being pleasured during sex is important for everyone, and should feel able to discuss it with their partner if they’re not. The idea of questioning one’s sexuality should be embraced and discussed, along with healthy ways to go about this. All of these things become much more possible once we have a space in which common concerns can be raised and addressed, in which students are taught how to have healthy sex, in which we grow accustomed to talking about sex, and it becomes demystified.

So in the spirit of practising what I’ve preached, I feel as though I should talk frankly about my experiences with the sex education that I received. In short, it sucked. It repressed me. It probably did more harm than good. Yes, I learned how to put on a condom. But I also grew so afraid of regretting sex that I put it off for much longer than I was happy with. All I had ever been taught was to be afraid of the emotions, the complications and the pressure without ever having been taught to deal with them. I never truly thought about the importance of experiencing sexual pleasure myself, or how I might achieve that as much as possible; I was too focused on experiencing the terrifying mystery of sex itself. I didn’t know how to explore my sexuality, how to embrace the sexual side of myself – or even that these were positive, healthy things to do. Chances are, if I hadn’t ended up surrounded by a particularly liberal and open group of people when I came to college, I would have remained repressed for a significant part of my life – and that is a hugely disturbing prospect. Maybe I am just an extreme example of innocence and ignorance, but at the end of the day no product of an institution that is legally obliged to provide sex education should ever be so afraid of something so natural. Irish sex education failed me, and as long as it continues to be entangled with religious doctrine, it will continue to fail.