O’Donovan Rossa was born in Reenascreena, Co. Cork in 1831 to Denis, a tenant farmer, and Nellie (neé O’Driscoll). He was a child during the tithe campaign which politicised people throughout Ireland on a level not seen since the United Irishmen’s organising during the 1790s. There is little doubt that the sense of empowerment felt by local communities during the tithe campaign as well as during the land struggles witnessed by Jeremiah in his youth had an impact on his coming-of-age. The Irish language was the language of his family and his national identity was the cornerstone of his own personal identity from a very early stage.

Both the immediate and long-term effects of An Górta Mór (1845-50) on Rossa and the Irish people as a whole cannot be understated. The deaths of 1.25 million people from starvation or disease and the forced emigration of over a million others, combined with the sights of countless evictions, land-clearings and police-supervised cabin-levellings, as well as the simultaneous continued export of wheat, barley and oats from Ireland for the profit aims of landlords (often absentees), undoubtedly shaped Rossa’s understanding of the world and triggered in real terms a realisation of the starkly exploitative, colonial and deathly nature of the relationship between his country and the ruling Westminster oligarchy and their financial masters. One of those to fall victim to the Great Hunger was Rossa’s father, Denis. The family was left bankrupt and everything they owned was put up for auction by Nellie. The following year, 1848, Nellie and the rest of the family, with the exception of Rossa, emigrated to the US.

Mugshot of O’Donovan Rossa while in custody.

At the age of twenty-five, in 1856, Rossa, who by then managed a shop in Skibbereen, established the Phoenix National and Literary Society (PNLS), which had as its aim, ‘the liberation of Ireland by force of arms’. Two years later, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) was founded on St. Patrick’s Day in Dublin’s Lombard Street. IRB founder and former Young Irelander James Stephens began a recruitment drive throughout the country and he visited west Cork the same year where he recruited Rossa into the IRB, bringing about a merger between the PNLS and the secret, oath-bound revolutionary organisation.

The purpose of the IRB was to achieve Irish freedom and introduce democracy to a country where a foreign aristocracy had long been entrenched in power. It was and remains impossible to separate the issues of national freedom and progressive politics. One without the other was understood by Rossa and those of his generation, just as James Connolly and the Irish Citizen Army would later understand, to be little more than, to paraphrase Connolly, changing the colour of the flag while England still rules you ‘through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country’. Very quickly Rossa took on the role of an IRB recruiter. He also organised moonlight pike and rifle drilling for IRB members in west Cork. A paid spy, Daniel O’Sullivan Goulda, working for the Royal Irish Constabulary, helped in the arrest and conviction of Rossa in December 1858. Rossa was held in Cork Jail until July 1859 when he was released on assurances of good behaviour.

In 1863, Rossa left Ireland for New York. There he assisted John O’Mahony, the Fenian Brotherhood’s founder, to strengthen that recently established organisation. He wasn’t in New York long before he took an opportunity to return home to become the business manager of the IRB’s newspaper, ‘Irish People’. He was arrested, on the word of a paid traitor, Pierce Nagle, before a potential rebellion in 1865 could take place. Rossa was found guilty of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment. In 1867, while Rossa was in jail, an IRB rebellion occurred, but a mixture of unwelcome factors, including insufficient leadership, bad weather and informers, forced its premature and unsuccessful end. Although the 1916 Rising is broadly taken to be the most important acts of rebellion in Irish history, and some anti-nationalists and revisionist ideologues consider it the only republican rebellion worth mentioning, 1867 should definitely not be forgotten. Nor should the Republican Proclamation of 1867. This proclamation exemplifies the degree to which Irish nationalism was and is based on democracy and inclusion of all sections of the nation, and is pro-actively devoid of any ill will towards the English people. The Proclamation states:

‘[W]e intend no war against the people of England – our war is against the aristocratic locusts, whether English or Irish, who have eaten the verdure of our fields – against the aristocratic leeches who drain alike our fields and theirs. Republicans of the entire world, our cause is your cause. Our enemy is your enemy. Let your hearts be with us. As for you, workmen of England, it is not only your hearts we wish, but your arms. Remember the starvation and degradation brought to your firesides by the oppression of labour. Remember the past, look well to the future, and avenge yourselves by giving liberty to your children in the coming struggle for human liberty.’

It was as part of that movement that Rossa found himself imprisoned. Treatment of Fenian prisoners in England was particularly rough, cruel and inhumane. Rossa was held in a number of prisons (Portland, Chatham and Pentonville), often in solitary confinement, on one occasion with his hands manacled behind his back for thirty-five days, forced to survive on strict, austere diets eaten from a bowl on the ground as if he were a dog. He also experienced being forced to sleep naked and his cell being stripped of all bedding. The cause for this degrading treatment was Rossa’s and other Fenian prisoners’ determined refusal to carry out prison work as if they were common criminals, and not the political prisoners or prisoners of conscience they and their supporters understood them to be. Irish republican prisoners have struggled continuously since the 1790s for recognition of their cause as a political and legitimate one. Refusal on the part of the British state, and from 1922 the partitionist southern state, to accept their cause as such has directly led to an expected, physical-force reaction from republicanism as peaceful ways forward were ardently blocked time after time. In prison, the issue of non-recognition of political prisoners or republican POWs has caused huge tension between prisoners and the authorities, culminating in the deaths of twenty-two republican hunger strikers during the 20th century.

Puck Magazine (a late nineteenth century US publication known for its anti-Irish sentiments) has as its 19th March 1884 a depiction of O’Donovan Rossa, with the caption ‘Gorilla Warfare under the protection of the American flag.’

While in prison, in 1869, Rossa stood as a candidate for parliament for Tipperary and was elected as the constituency’s MP. Just as fellow nationalist and former Young Irelander John Mitchel experienced after his election as MP for Tipp in 1875, the British government ruled Rossa’s election null and void. So when modern day Redmondite moralisers, like John Bruton and fellow IPP sympathisers, lecture us about the fantasy that Ireland experienced upstanding and empowering democracy under monarchical British rule or, as they’d see it, in partnership with Britain as an equal member of the UK, ask yourself why then were Mitchell and Rossa barred from being MPs following their endorsement by ballot box (and remember also, whatever democracy existed at the time was known to no woman and to less than fifty per cent of the adult male population)?

Rossa was released as part of an amnesty offer in 1871 which involved his exile from Britain and Ireland alongside four other Fenians. Rossa headed to the US. Years of brutal prison regimes undoubtedly took their toll on him, as they would on anyone. Yet, throughout the rest of his life Rossa remained steadfastly committed to the cause of Irish national freedom and democracy, not wavering once, despite what the Daily Telegraph in 1915, without substantiation, alleged that he became a Home Ruler, something Rossa would have understood, quite rightly, to be a half-heart, a traitor and the embodiment of surrender to his life-long enemy, the British government. This allegation was baseless conjecture and mud-slinging which was disrespectfully and disgracefully repeated at his graveside on Saturday morning during the state centenary event. The state sought to do the impossible, to separate Rossa from his politics and even impose upon him a political outlook he, at least, was uneasy about and, at most, viewed with limitless contempt. That event was about making today’s Home Rulers more comfortable than the truth would ever allow.

In America, Rossa took charge of a ‘Skirmishing Fund’ set up by the Irish nationalist group Clan na Gael. The money raised would be used to make plans for a bombing campaign in Britain a reality. The fund allowed for the numerous bombings of cities including Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and London. The most significant Fenian bombings would be those of (Old) Scotland Yard (replaced by New Scotland Yard), the Palace of Westminster (which was again bombed by the IRA in 1974) and the Tower of London (also bombed again by the IRA in 1974). As well as ensuring money remained available for such activity and acting as a spokesperson for the campaign, Rossa established a ‘dynamite school’ in Brooklyn. Spies and informers, especially the notorious ‘Red’ Jim McDermott, proved to be the downfall of the bombing campaign and the cause of many arrests, including that of the 1916 Rising mastermind and O’Donovan Rossa funeral head-organiser, Tom Clarke.

In 1885, at Broadway, O’Donovan Rossa survived an assassination attempt by a bipolar sufferer, Yseult Dudley, who shot him multiple times. Dudley when questioned by the police, replied, ‘I am an Englishwoman and I shot him because he was O’Donovan Rossa, you know the rest.’

Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa (1845-1916). Wife of Jeremiah from 1864 to 1915. She also devoted her life to the struggle for Irish freedom, and was particularly vocal on the issue of political prisoners. During his final years, Mary Jane took over the role of editor of the United Irishman.

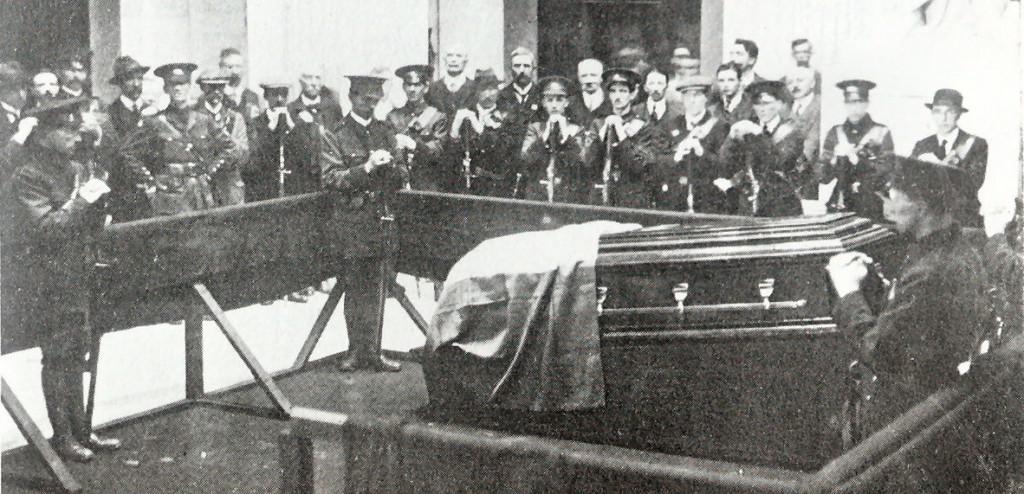

Rossa returned twice to Ireland. The first time in 1894 when he arrived in Cobh, embarked on a speaking tour across the country and unveiled a memorial to the Manchester Martyrs in Birr, Co. Offaly. The second time was in 1905 but when his wife of forty years Mary Jane, fell ill, he returned to America. His own health began to deteriorate and he experienced increased levels of dementia. Rossa died in Staten Island on 29th June 1915. On hearing of his death, Clarke said of Rossa that ‘had he chosen a time to die he could not have picked a better time’ and his words to John Devoy of Clan na Gael were ‘send his body home at once’. In organising the funeral, Clarke asked Patrick Pearse, the IRB’s newly found public spokesperson to make the funeral oration ‘as hot as hell’. Pearse did not disappoint, entering into the history books his famous graveside speech which was to help spark the seeds of rebellion in the coming year.