“Legend has it”, a 2021 Trinity News article claimed: “there is a network of underground tunnels beneath Trinity.” In this anniversary issue, Trinity News decided to delve deeper into the reality behind this enduring myth.

Generations of freshers have been told about these underground tunnels and cellars, where students would supposedly meet in secret, sneak into Trinity Ball, or even – according to a legend dating back to the 1980s – steal wine from the College stores. But where were these secret passageways? “We all thought there were [tunnels] under Front Square”, one alumnus who graduated in the 1980s shared with Trinity News, “but also one running from the Old Library to Berkeley”. The belief that there is an underground route under Front Square has endured for decades; a poster on boards.ie (an Irish chat forum) wrote in 2008 that “whenever the snow falls, you can see the route of one tunnel running… from the east side of the Chapel to the side of the Exam Hall”, because the snow above this track melts faster. However, this claim of an L-shaped tunnel has been debunked; rather, there’s an underground water pump that heats the pavement in this specific area.

What students call the “Front Square” actually encompasses two separate spaces: Parliament Square (the Front Gate to Campanile) and Library Square (the Campanile to Rubrics, the recently refurbished redbrick buildings). Such a distinction was made by Linzi Simpson, a prominent Dublin archaeologist, who wrote about the excavations of Trinity College Dublin in a Medieval Dublin Symposium in 2011. Simpson suggests that there may have been some underground activity as far back as the sixteenth century as Trinity College stands on the site of the medieval All Hallows Church. The outer walls of this church were repurposed as the original College Quadrangle in 1592 and this is why excavations in 1998 uncovered five skeletons in Library Square: the All Hallows Church’s graveyard site stretches across the lawn.

“Unfortunately major tunneling seems to have been beyond the means of these medieval monks”

Students might assume this means there are some underground structures here, but unfortunately major tunneling seems to have been beyond the means of these medieval monks. Even the monastery which became the Quadrangle was very small, its walls limited to the left-hand side of Parliament Square as you enter via the Front Gate. If there were ancient tunnels here, the 2011 excavations of Parliament Square – carried out in order to lay cables – would have exposed them.

While there may be no tunnels in Front Square, there certainly are cellars. In correspondence with Professor Emeritus and author of “Early Residential Buildings of Trinity College Dublin” Andrew Somerville, Trinity News learned that a number of buildings in the area used to have cellars beneath them. Images of College in the 1600s and 1700s show that buildings were regularly pulled down and built over. In Somerville’s book, bills and receipts confirm the existence of these cellars. For instance, in 1721, tradesmens’ bills amounting to £829 were recorded for “new cellars and buildings over them.” A bill from 1754 for bricklayers working in Library Square references the construction of foundations for cellar steps, and the building of walls that would divide the “coal holes” used to supply the Rubrics with coal.

These storage “holes” could have been large enough for students to use for more than storing coal, although there’s little evidence of this. Today, these underground spaces have probably been closed up following the recent refurbishment of the Rubrics.

Palliser’s Building, which would have stuck out into the middle of Parliament Square from the left just before the dining hall, was known to have a cellar where undergraduates drank and were served by butlers. There is even an anonymous poem about the cellar dating back to 1737. However, when this building was demolished in 1788, could this cellar have survived? The short answer is no. When the older buildings from the 1500s to the 1700s were demolished in Parliament Square, Somerville told Trinity News that these plots became open space. There would have been no need for any cellars or tunnels to remain there. In fact, College took all the bricks from these structures to re-use or sell.

However, there are some remains of these old buildings under Parliament Square, left behind when the old “Great Court” of College was pulled down. For instance, there are cellars under the “north range of Parliament Square”, stretching from House 10 to just short of the door to House 8. Underneath the “Chapel and its flanking houses”, there’s a crypt, in which a statue of Luke Challoner – one of the three founding fellows of Trinity – can be found. Today, the door to the crypt can be found to the left of the Atrium. These sites, which Somerville visited and photographed for his book, could have been the basis of the rumours about the famous secret tunnels in Front Square.

One final feature of “underground Trinity” is the huge water tanks under the South Lawn of Library Square, dating from the 1830s, and the pipes which brought this water to bathrooms and kitchens across campus. Yet it is doubtful these structures would ever have served any purpose other than that of transporting water.

“It’s possible to walk all the way around Fellow’s Square without going outside”

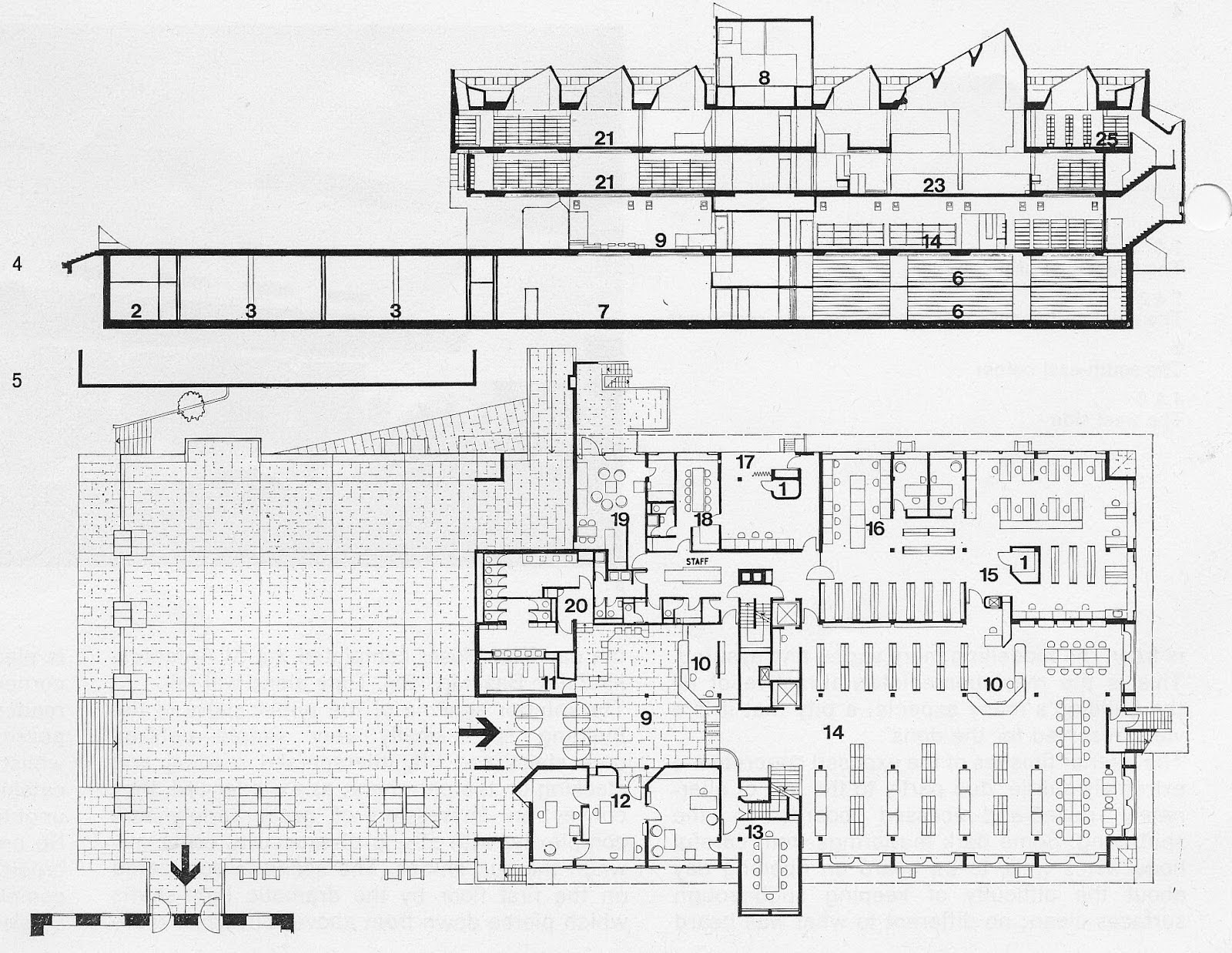

Moving on to the Library tunnels, Sub-Librarian Peter Dudley was able to confirm the existence of underground tunnels connecting each Trinity Library and Reading Room. “Quite a lot of the Library infrastructure is underground,” Dudley told Trinity News. He explained that the Old Library and the BLU complex are joined by a tunnel that runs alongside the podium in front of what used to be the Berkeley Library; this is the largest tunnel, and was opened in 1967. The tunnel ends in a cylindrical structure and a spiral staircase which was inserted into the Old Library. Looking at the original ground floor plan of the Berkeley Library, the path to the Old Library is clearly visible, branching off to the right, underneath the podium. A tunnel used for transporting books connects the Old Library and the 1937 Postgraduate Reading Room: “A reader who wanted to consult something would put in a request,” Dudley explained, “and a (library) worker would bring the book.” As you might expect, this tunnel is open only to staff, with Estates and Facilities now using it for storage. There is also a tunnel connecting the 1937 Postgraduate Reading Room and the Long Room Hub – though it’s really more of a corridor, and also for staff use only – and a tunnel between the Long Room Hub and the Arts Building which can be accessed through the Edmund Burke theater. “It’s possible to walk all the way around Fellow’s Square without going outside,” Dudley said.

While stories about tunnels under the libraries are true – they were built relatively recently – it seems the idea of an entire subterranean network underneath College can be thoroughly debunked. As Andrew Somerville explained to Trinity News, while researching for his book, he never found evidence of anything “old and long in Trinity”. Peter Dudley added that Trinity’s campus was built on what would have been at the time “very swampy ground”, which makes any large-scale excavation or underground building nearly impossible.

If a student wants to feel like they’re exploring the mythical Trinity tunnels, Dudley recommends going to the Early Printed Books section underneath the BLU complex. This section is in fact the tunnel that connects the new and old libraries. However, he warned that as renovations for the Old Library begin, the Early Printed Books section will likely be relocated to the basement of the Ussher — so students should go and visit now, before they lose their only chance to step inside a real Trinity tunnel.