Recently, hate crime law (HCL) has seen increasing popularity within the Irish anti-racist movement. The Irish Network Against Racism (INAR) proposed the Love Not Hate campaign calling for HCL in 2019. The main goal of this campaign is to introduce the Criminal Law (Hate Crime) Bill 2015, which focuses on crimes that were motivated by racism and other forms of discrimination. INAR concluded that with the implementation of this bill, the government will push down harder on perpetrators giving them enhanced sentencing.

The Irish Council for Civil Liberties launched the Lifecycle of a Hate Crime report in 2018 which outlines actions the State must take to “protect” vulnerable and marginalised communities from instances of harm. Additionally, they highlight the lax nature of the Irish Government in regards to HCL. Through 38 interviews with criminal justice professionals, they concluded that there’s little guidance available for prosecutors when met with a hate crime element in the criminal justice process. They argue for hate crime legislation to be implemented to act as a “message crime”, which ostensibly sends out the message to the public to not commit hate crimes. The closest account of proposed laws in the Irish legal system is the Criminal Justice (Victims of Crime) Act 2017, which enacted a socio-legal procedure whereby individuals impacted by crime are given certain rights. Namely, the right to an individual assessment of their needs and preventative measures to protect them from further victimisation. The Irish state is not equipped to deal with instances of prejudice such as racism, transphobia, homophobia or classism. However, we must ask ourselves a very vital question: does enacting hate crime laws effectively deter these crimes, or even fundamentally challenge the systems which uphold and reproduce this oppression?

“Ireland was not a coloniser but the Irish were involved in upholding slavery, which is pitiful considering the Irish could have extended solidarity with other colonised peoples instead.”

To assess whether these laws work or not, we need to look at the origins of oppression in order to gain a better understanding of how we can actively fight against racism. Racism as we know it, began through racialised social organisation. This broadly began in the 15th century, when Europeans colonised people who were consequently racialised by their oppressors. They did this in order to hierarchically manage society for their own benefit through slavery, extraction, and profiteering. This legacy of colonialism still lingers. Ireland was not a colonial power in the same fashion as many other European countries, but the Irish were involved in upholding slavery, which is pitiful considering the Irish could have extended solidarity with other colonised peoples instead. Ireland benefitted from the trade of African slaves through producing merchants and helping expand slave colonies. Irish history presents how the Irish calculatively made themselves white through labour competing with the Black population in the States and supported slavery. Noel Ignatiev wrote a ground-breaking book, How the Irish Became White, which highlights how the Irish constructed themselves as “white” post partial independence. Mechanisms such as labour unions, the Catholic Church, and electoral politics helped to achieve their goal of becoming white. Since history informs who we are today, and what the State has become, it will take a lot more work than putting a band-aid over an inherently exclusionary and discriminatory state.

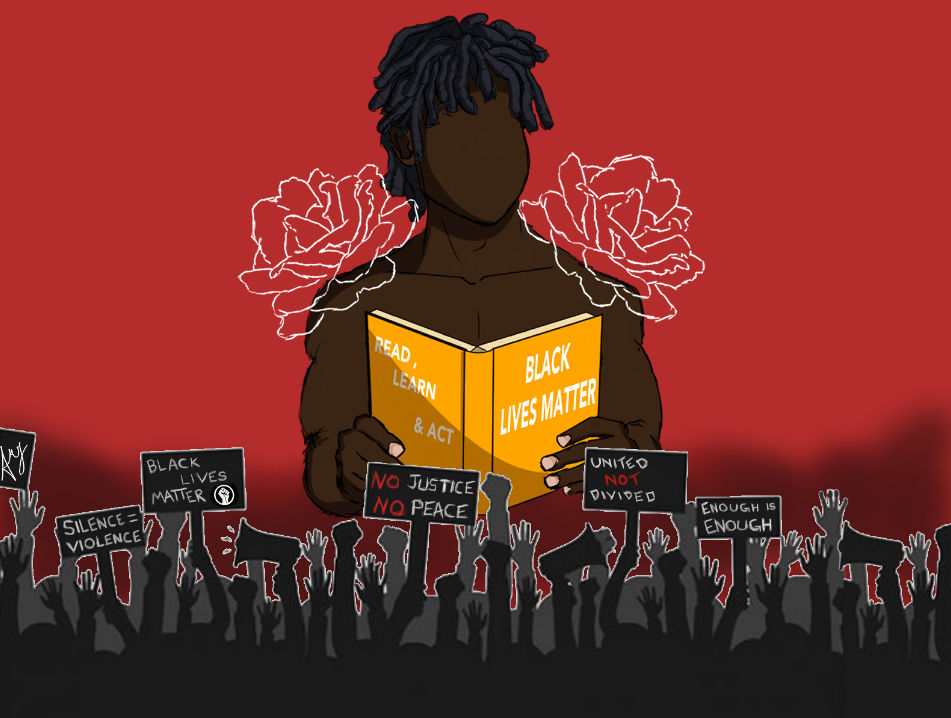

With this in mind, it is clear to see how the extension of the same system that harms us will not protect us. Hate crime legislation is symbolically used as a sign of progression. Advocates of this legislation argue that we need to “crack down” on personal incidents of abuse in order to deter further instances. The proposal that HCL works fails to acknowledge how there is a body of evidence which shows that these laws have not deterred violence in other countries such as the US. Furthermore, it is an outright refusal to address the fact that the police systemically targets the most marginalised communities, which are often not comfortable with reporting to the police in the first place. It takes away from the pivotal work of dismantling the dominant culture that breeds this harm. The reality is, these performances of hatred come from deep-seated issues within the State.

“Furthermore, it is an outright refusal to address the fact that the police systemically targets the most marginalised communities, which are often not comfortable with reporting to the police in the first place.”

Fine Gael TD, Charles Flanagan, proposed amendments to the Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Act 1989. This will take into consideration the report published by the Irish Council for Civil Liberties on changes to the legislation which prioritise hate-motivated crimes. These views include “better reporting and recording of hate-motivated crimes, enhanced procedures for the investigation of such crimes, and training and guidelines for prosecutors”. Conservative politicians calling for HCL is paradoxical while doing nothing tangible for genuine change. It’s time to stop relying on these people for justice and safety. As Adrienne Maree Brown states: “if the original conditions were unjust, then returning to those original conditions is not justice.” Hate crime law sweeps the symptoms of an oppressive social structure under the rug.

In the Irish context, the majority of prisoners in Mountjoy Prison come from areas marked by high levels of socio-economic disadvantage. Women from the Travelling community are disproportionately visible within prisons. 22 percent of women in Irish prisons are Mincéirs. 24 percent of people incarcerated in Ireland are non-nationals. Migrants may not interact with the police when they have experienced harm because they’re afraid of being deported. Since we want to see a better world where less people are hurt, I cannot invest energy into campaigning for hate crime legislation to be introduced into the same system that already enacts so much harm to those marginalised most.

“22% of women in Irish prisons are Mincéirs. Another harrowing statistic is that 24% of people incarcerated in Ireland are non-nationals.”

These proposed laws would add to a legal system which already protects the unjust International Protection Act 2015, which allows the state to deny refugee status to applicants via the “inadmissible application” dimension of said act. Furthermore, it adds to the same institution that by legal definition sustains Direct Provision (DP). This process, made visible by the Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland (MASI), has been deemed inhumane by refugees and a “severe violation of human rights” by the UN. Arguing for HCL is a rejection of these statements by the marginalised members of our society, who ultimately see the flaws inherent in our legal system.

We should not add more laws aimed at protecting our communities into the same system that thinks it’s alright to deport a nine year old boy who was born in Ireland but does not have Irish parents. Let’s not add more laws to a legal system which already protects DP, which allows businesses’ to profit from grossly inadequate living arrangements. The answer to harm is better conceived of through transformative justice. Let’s shift the focus to alternative pathways to justice outside the carceral state, in order to sincerely support those most affected.