Over the course of six years, from 2016 to 2022, Cork-based artist Kevin Mooney collected work for the Revenants exhibition, on display from December 1 to March 5 at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA). Curated by Sarah Kelleher, Revenants explores Mooney’s continued interest in a “speculative art history” of the Irish diaspora through images of history, horror and observation. Mooney uses the medium of painting to reimagine the pieces of Irish history that were overwritten by empire and colonisation, but also represents that altered history and what it means for present Ireland. In acknowledging the gaps in Irish history, he calls the viewer’s attention to tainted versions of the Irish body and psyche that are polluted and overburdened by folklore made mutant and absurd. The result is an exhibition that invites horror and awe through brilliant, monstrous images of the disfigured and rearranged human body. If the human body can represent the history of Ireland, Mooney imagines that history as oddly mutilated and reassembled.

Revenants simultaneously marks historical gaps and recreates Irish history, assigning figures and abstract human forms to a new context. Mooney’s awareness of disparate traditions and his subsequent inability to reconcile them places him in an unusual artistic position. He is paralysed by these conflicted histories and superimposes history onto the familiar human body. Mooney’s new bodies become things of horror and mystery, sometimes anatomised and, at other times, metamorphosed into mythological figures, often with multiple heads or no heads at all.

“The new body in Mooney’s work is genderless and physically amorphous.”

The most striking example of this is Ilcruthach (2021), which depicts a bi-gendered, triple-headed figure. A dark background focuses our attention onto the figure, who stands like the Vitruvian man with palms facing out and a linear body. This figure has three sets of hollow eyes, and the torso is overcome by curling, bubbling rivulets of folding skin as the two heads on either side droop and change to a sickening green. The new body in Mooney’s work is genderless and physically amorphous. It is shocking to look at and invites a strange horror and admiration for its nudity, sincerity and state of constant transformation.

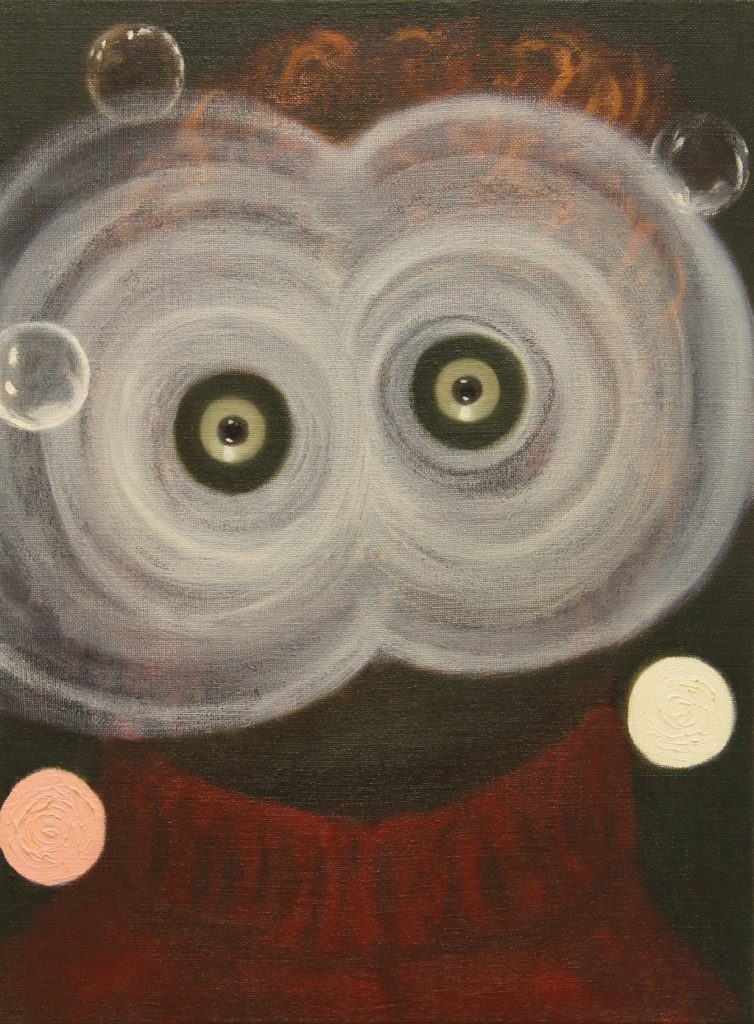

Mooney’s work in Revenants considers how Irish identity was created, through the eyes of the Empire, and how ghost stories can be as revealing to us as they are disturbing. One aspect of the exhibition that haunts its viewers is the presence or absence of humanoid eyes, from the headless eyes of Peasant (2018) and Orbs (2018) to five cyclops figures in Blighters (2018-21). Anyone with an interest in motifs will have noticed Mooney’s striking use of eyes and eyeballs, hinting at the anatomisation of the senses. In particular, sight because we observe paintings with the eyes; it is the preferred sense for his medium. However, Mooney also hints at the possibility and impossibility of observing history.

“Mooney’s work in Revenants considers how Irish identity was created through the eyes of the Empire and how ghost stories can be as revealing to us as they are disturbing.”

Mooney’s eyes are all-seeing; they do not stare into nothingness but stare directly at you as you wander round the exhibition. They unsettle you but also hold you accountable. You are seen. The painting from which the exhibition takes its name, Revenants (2022), is only recognisable as a portrait because of its two intelligent eyes. The faces in the exhibition are abstracted, recognisable only as somewhat human forms and shapes. Sometimes they are not recognized and, as Mooney desires, we lose the human aspect to the work.

These disconnected eyes create an unsettling and uncanny effect as you pass from room to room at the IMMA exhibition. They are traumatised eyes, paying witness to an odd loneliness and an isolated lamentation for lost pasts and futures. The two best examples of these watchful eyes are in Orbs and Peasant. Orbs centres on the portrait of a person wearing a dark red jumper with curly red hair. The figure is completely swallowed in darkness while its eyes are given a sequence of growing pale circles ‘orbiting’ them and radiating outward. Behind the figure is darkness and silence. The eyes glisten in the painting and stare intensely at you, completely removed from any type of human face that would otherwise bring them a familiar comfort or recognition. For Mooney, it is better that we do not find that comfort or familiarity in the face; rather, we realise the impossibility of recognising the other and instead become unsettled by them. Much like the effect of staring at your own face in the mirror for long periods of time, the background is tuned out and the eyes come into intense focus. They are the centre of everything. Orbs resembles the gaze of a great grey owl, or perhaps a barn owl. It has an animal-like intensity without the hollowness of staring at nothing.

“The layer of marks seems to separate us from the eyes like a sheet of glass, perhaps hinting at our proximity to history, always present but unreachable.”

Peasant is a similar painting, with two looming eyes lost behind a patternless cluster of orange marks and dashes. Behind the layer of marks is darkness, with a roundish shape that could be called a human skull. There are three eyeballs in this painting, two of which seem to be with one skull and another eye floating down below. A marked difference appears in the temperament of this work, in which the eyes are not gazing intensely, but with horror and fear. They are uncertain eyes, looming, troubled and troubling to see. The layer of marks seems to separate us from the eyes like a sheet of glass, perhaps hinting at our proximity to history: always present but unreachable.

For more information about the IMMA exhibition of Kevin Mooney’s work, see imma.ie.

To look at more work by Mooney, visit his personal website kevinmooney.org.