BookTok is missing the mark

Luke Fox Whelan

It must be doing something right. Now four years on from the pandemic which brought it into existence, BookTok has shown itself not to be a fad. Rather than the killing of books by the scourge of phones and social media, as predicted by Facebook memes from the 2010s, they have reached a synthesis: a community passionate about reading, about taking pride in a huge bookshelf. BookTok has launched careers. Reading and social media is synthesised in five-second, rapid fire reviews of a truly staggering number of books read by these modern book reviewers, certainly putting my monthly bibliography to shame.

There’s something concerning in this output, though. The knee-jerk reaction to BookTok is often that they’re bad romance schlock, low art if ever such a thing existed. However, I believe there are more substantive, less snooty and patronising ways to criticise it. Not all books have to be candidates for an English degree reading list. Looking down on no-strings-attached enjoyment is one surefire way to discourage reading, which is something none of us want.

These books should be assessed on their merits like any other, which is where my defence of them ends. The platform’s biggest success story, Colleen Hoover, has been accused by critics of romanticising abuse and violent power imbalances in relationships. Another prolific BookTok success, Cassandra Clare, is haunted by various scandals including credible claims of plagiarism in her published books, as well as relationships bordering on incest (which originally were incestuous in the fanfiction she adapted them from).

These aren’t banned topics, but the issue is their romanticisation. Discussing how we should interpret this work also reflects the worst aspects of the platform that popularised them. Shocking themes and relationships sell, just as extreme emotions in silent reviews of book hauls draw in TikTok engagement. Criticism of authors and their past work turn into drama alert callouts. Allowing BookTok to be ignorant about the rest of the literary world will only breed these bad habits.

The authors that reach the star position of Hoover and Clare are also generally white. BookTok is the pinnacle of success for modern self-publishing, showing the power of a direct connection with an audience. Arguably, self-publishing’s greatest virtue is an ability to spotlight diverse authors who may find it harder to publish in the corporate culture of the major publishing houses.

Yet this does not happen on TikTok, or at least not to the extent that industry insiders expected at the outset of the BookTok phenomenon. Speaking to Tyler McCall for The Cut, author Nisha Sharma expected, as did her peers in publishing, that a young adult audience which craved diversity would keep those tastes as they matured. Instead, “we’ve almost seen a regression.”

Perhaps it’s not white readers and content creators to blame, but the algorithm. Algorithmic racism is well-documented, and BookTok is no exception. Some Black creators strategise around this — it is a career, after all, and sponsors have to be satisfied with view counts, as Breana Newton details in the Cut article. Some forge ahead, writing and highlighting the kind of Black stories they want to see more of. But this comes with other challenges. Long-term trends of racism in romance genres carry over, and when general audiences see Black books reviewed, they push trauma over romance.

This explosion in self-publishing is not making outsiders heard, it’s making certain genres and groups hegemonic and policing the borders of those genres strictly, as algorithmically successful books fit neatly into established tags.

There is one final issue with the other kind of BookTok book: the BookTok sad girl fiction canon. This is the polar opposite of the kind of romance above. For better or worse, these are more literary, well-established books that could have an audience outside this platform — think Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year Of Rest And Relaxation, or Sally Rooney’s Normal People. Unlike the romance books, these are very limited. This is a reading list of essentials. And yet, by completing this checklist you become a literary aficionado. To hold up a stack of these books to the camera, spines fully intact, or have them tactically strewn across an unmade bed, instantly communicates the tragedy of being a tortured intellectual.

BookTok is improving reading levels, in the way a government might by investing in education. But its message of a quick fix to media literacy should be at least viewed with suspicion.

BookTok is a literary revival to be celebrated

Nina Crofts

I wouldn’t be the reader I am today without BookTok.

My secondary school reading list had plunged me into a reading slump. At 15, I was bored of atmospheric classics like Pride and Prejudice and The Grapes of Wrath. Frankly, I was sucked into fanfiction as my escape during the pandemic, or graphic novels. I’d read them off of my phone in between online classes.

BookTok seeked to appeal to that hunger, a type of fiction many teenagers were craving while locked inside. Many BookTok books of that early era highlight young love, or feature riveting plot twists. A niche online subcommunity had formed to platform the ‘hidden gems’ of modern literature and propel them to number one, and it took off quickly. BookTok also introduced me to classics I can actually appreciate. Emma and East of Eden have been organically rediscovered by TikTok influencers, who saw the deficits in our secondary school English curriculum.

One of the reasons media consumption, be it films, novels, or television, is so rewarding is the connection we share with others when digesting it. Letterboxd and Goodreads serve as online platforms to express a love for your favourite media, and I view the extended world of BookTok as just an expansion of that.

A lot of the critiques of BookTok, frankly, lie within an intrinsic desire to gatekeep. I remember it, feeling superior at 14 years old for reading more than just school assigned novels. In adulthood, those who had a continued passion for reading may simply feel superior for that and wish for it to stay their own niche interest, for “intellectuals.” But reading has become so much more accessible recently, through more diverse genres and stories to a rise in audiobooks, and it feels strange to gatekeep something that so many can enjoy.

Don’t get me wrong, Colleen Hoover books aren’t my thing, and for a multitude of reasons can be seen as problematic. I won’t negate that some realms of BookTok I may find strange, or even off putting. BookTok has sides to it, and it’s unfair to generalise; I’ve found myself receiving far more historical fiction recommendations recently, while others may be wading in Bridgerton-esque romances.

For some people, those books are an escape and catharsis they never knew could be reaped from picking up a book. The literary community needs to realise that gatekeeping literature, and shaming first-time readers for appreciating introductory level books, is a surefire way to keep reading elitist and assure stagnation in content production.

The more people who have discovered reading can be their thing, the better. A healthier, more empathetic, less stressed population feels like a strange thing to be mad about, and I find it encouraging that publishers houses are now looking for unique talent to find ways to bring non-readers in as consumers. Some of my favourite BookTok videos are “if you enjoy this…you may like this” videos, which are great ways to acquaint people with new genres or styles they might not have explored.

As selfish as it may seem, too, BookTok has helped me to curate my TBR (to be read) list to be a lot more complimentary with my style. Where I used to scour Goodreads, not knowing which reviews to trust, or ask my fantasy loving friends for recommendations of “fantasy-book-recs-that-weren’t-really-fantasy,” BookTok manages to provide much more pointed recommendations that I actually enjoy (turns out I just don’t like fantasy).

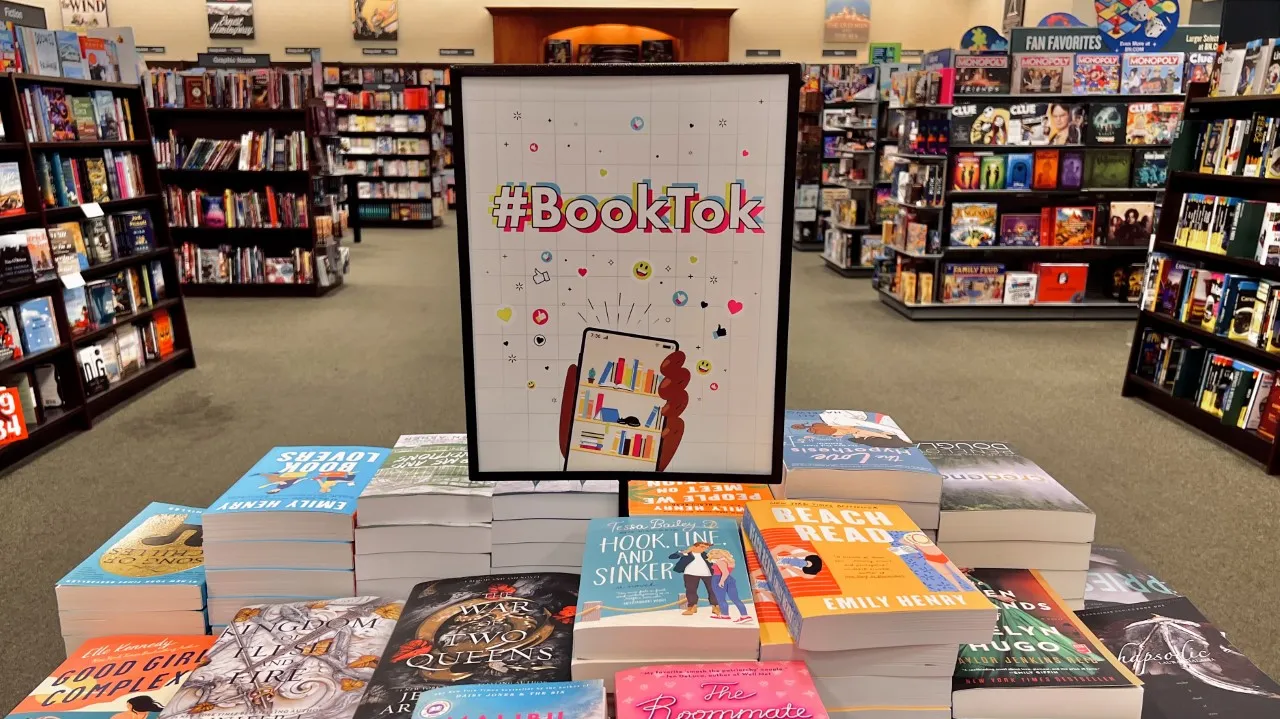

All in all, I believe that BookTok has massively revived the literary community, which I can’t see as anything but a positive. It has encouraged diversity, both in representation and style, and brought in new readers in droves. Where the bookstore chain Barnes and Noble was on the verge of closing in many states, they have in fact been adding more stores in recent years. And, if not for BookTok, I probably wouldn’t be as enthusiastic about reading as I am now. What was once a chore is now a reward, and that’s something to celebrate.