When reporter Charlie Bird began his career at RTE, he carried a dictionary in his pocket. He found himself constantly searching for the spelling of words, and also their meaning, to make sure he was using them correctly. When I began my job as deputy comment editor of Trinity News, I googled synonyms for various words, fearing I was coming across too strong in my articles, trying not to upset anyone.

My plan, unfortunately, did not work. In fact, I have upset some of the subjects I have written about. Following the publication of my article about the campaign of TCDSU Welfare and Equality Candidate Nathan Harrington, he made a post discussing “misleading and defamatory” articles within the press. When grilling Brídín Ní Fhearraigh-Joyce about the mechanics of her manifesto in the race for University Times Editor, I threatened to cancel her interview mid-way, due to her scrutiny of my questions, which had been sent to her in advance.

Despite this, these are the two articles of mine that have received the most attention, feedback and discourse this year. Had I attempted to soften my language, or had I followed through with the cancellation of that interview, those articles would not have come to fruition.

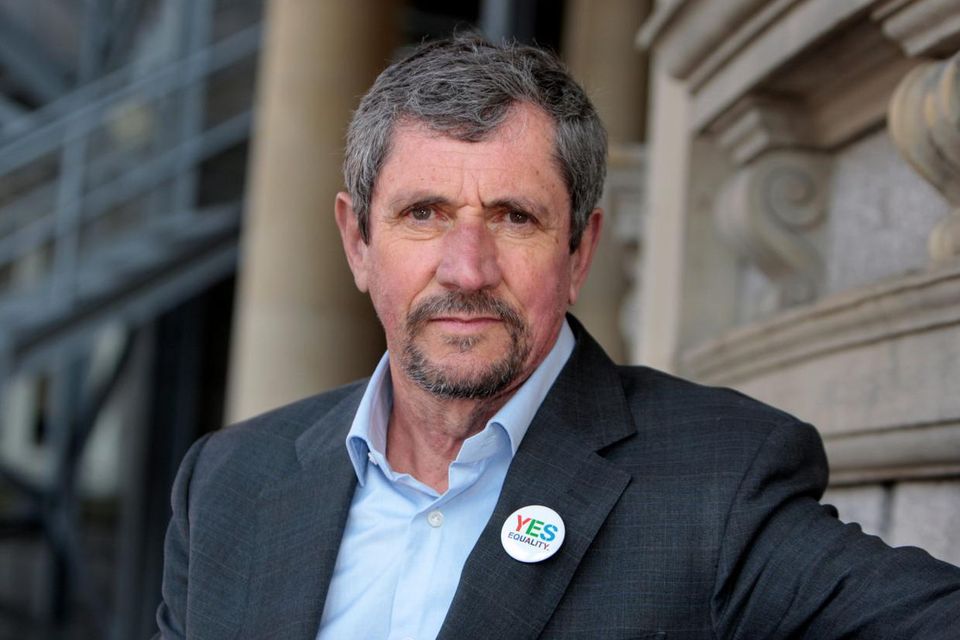

Upon his death in March, Charlie Bird was described by RTE as the “man who brought the world to so many living rooms”. Acting as the IRA’s sole point of contact with RTE during the Troubles, Bird scrawled the details of their ceasefire announcement into a pocket sized notebook, before announcing it to the rest of the country. I can only dream to achieve a position similar to that of Bird’s in the sphere of journalism. I may never bring the world to any Irish living room. For now, however, I can bring the Student Union closer to students. I can also bring political affairs closer to the uninformed student. That, at this point in time, is my goal.

Bird described his journalism as “political, without a capital ‘p’”. Though he was driven by a “social conscience”, his aim was to bring the facts to the Irish people. In an interview with the Irish Times, he noted that he grew up amongst injustice. He saw “people in Dublin without proper housing, the Vietnam War, the anti-apartheid movement”. This, to him, was the “backdrop of [his] life as a teenager”. Though driven by these injustices, he was aware that he had a job to do when it came to reporting: deliver the facts in an impartial manner.

“Of course, this is no longer the era of Charlie Bird”

Of course, this is no longer the era of Charlie Bird. Pocket-sized notebooks have been replaced by audio recordings made on phones, and paper dictionaries have been replaced by Google. To describe journalism as “political without a capital ‘p’”, especially as a student journalist, simply feels wrong today. Amidst increasing political participation, in Ireland and abroad, people don’t just want the truth laid out for them, but an opinion for them as well. Young people, in particular, crave actionable intelligence. They want to get the most liked comment under a news post, or to sound intelligent in a tweet about the goings-on of the world. We no longer search for the facts, we search for conceptions, from which we can confirm our own bias about a story, or from which we can argue against.

In the search for conceptions, we have lost the ability to recognise facts for what they are. When Trinity News reported on a petition was launched to impeach TCDSU President László Molnárfi, one comment accused the paper of becoming “Fox News”, while another accused journalists of showing “allegiance” to the “interests” of Ireland’s biggest news companies. Neither commenter acknowledged that the paper was simply reporting on the happenings of the college, but both comments received likes of approval from other students.

“Political discourse can only be effective when we seek the facts”

This is not to say that the media, including Trinity News, should not be subject to scrutiny. If we cannot foster discourse, then what is the point of our vocation at all? People have a human right to access information, and as journalists, we play a role in facilitating this. But rights come with responsibilities. Political discourse can only be effective when we seek the facts. If students can not recognise the difference between a report and an opinion piece, I fear for the future generation of voters.

As the Union becomes more political, in particular with the handing over of power from Molnárfi to Jenny Maguire, it has, and will continue to, push the boundaries of what student journalism can achieve. This is not limited to the role of student journalists, but the role of the students in their interactions with student media. The Trinity News Instagram, in recent weeks, has seen comments telling journalists to “touch some grass”, or calling articles “disgraceful”. Whether you agree with an opinion piece or not, telling the journalist to “touch some grass” does little to foster political discourse, and does more to silence the valuable voices of student journalists. When you place the value of composing a witty comment above recognising fact as fact and opinion as opinion, you move further away from the democratic ideals encouraged by our Union, rather than closer.

Maguire’s election will certainly continue the pattern of increased political discourse in the College, be that on campus, or within the comment pages of Trinity News. Her commitment to carrying on the work of Molnárfi, while also being the “loudest, most annoying voice” in the room, will certainly be contested by many students. How we, as student journalists, decide to approach such debates, will be a testament to our integrity within our roles. As the Union attempts to move away from the Constitution’s apolitical stance, student journalists at Trinity will certainly be kept on their toes. How you, the reader, reacts however, is also a testament to your own democratic values.

It is these challenges, however, that make student journalists better at their jobs. Never did I expect to be the one being grilled during an interview that I was conducting. Nor did I expect my work to be described as “defamatory” when I was referring to statements made by the person I was writing about. I also never expected students to message me to thank me for highlighting the issues I was writing about either, or mentioning that they had discussed my article with their friends at lunch.

When Charlie Bird stopped carrying that dictionary around with him, he became Ireland’s best known reporter. From showing up on the doorstep of disgraced Anglo Irish banker David Drumm, to being violently attacked at a Loyalist March in 2006, he stopped at nothing to bring a story to the Irish people. When I stopped anxiously googling synonyms, I found my voice. When I pressed for questions, I got the answers. Some of my best articles of this year were only written when I stopped overthinking, and approached them with passion, anger and a determination to contribute to student discourse.

The best thing I’ve done for my journalism career so far was to take a leaf out of that pocket-sized notebook.