Although our culture claims to celebrate individuality, this sentiment is about as genuine as the latest Players production. While the narrative of acceptance may appear true to life – if you squint – the arts block uniform and drinking culture will leave you sitting in the wings if you don’t adhere to its mould.

To be sure, the cast standing in the spotlight’s glare is unique to the naked eye. If you assess the stage, you will note many are costumed in the 90s fits warranting their Campus Couture feature, have dyed their hair, and keenly make quirky pronouncements about communism and mental health. Also, these adepts generally meet conventional beauty standards and are neither emotionally draining nor radical enough to make people feel guilty about their complacency. Likability correlates with this neatly packaged difference. The reality, of course, is that the spotlight’s glamour is elusive. Most of us have no idea what we’re doing even if we find ourselves onstage, seeking fulfilment like dancers awkwardly out of time with the music.

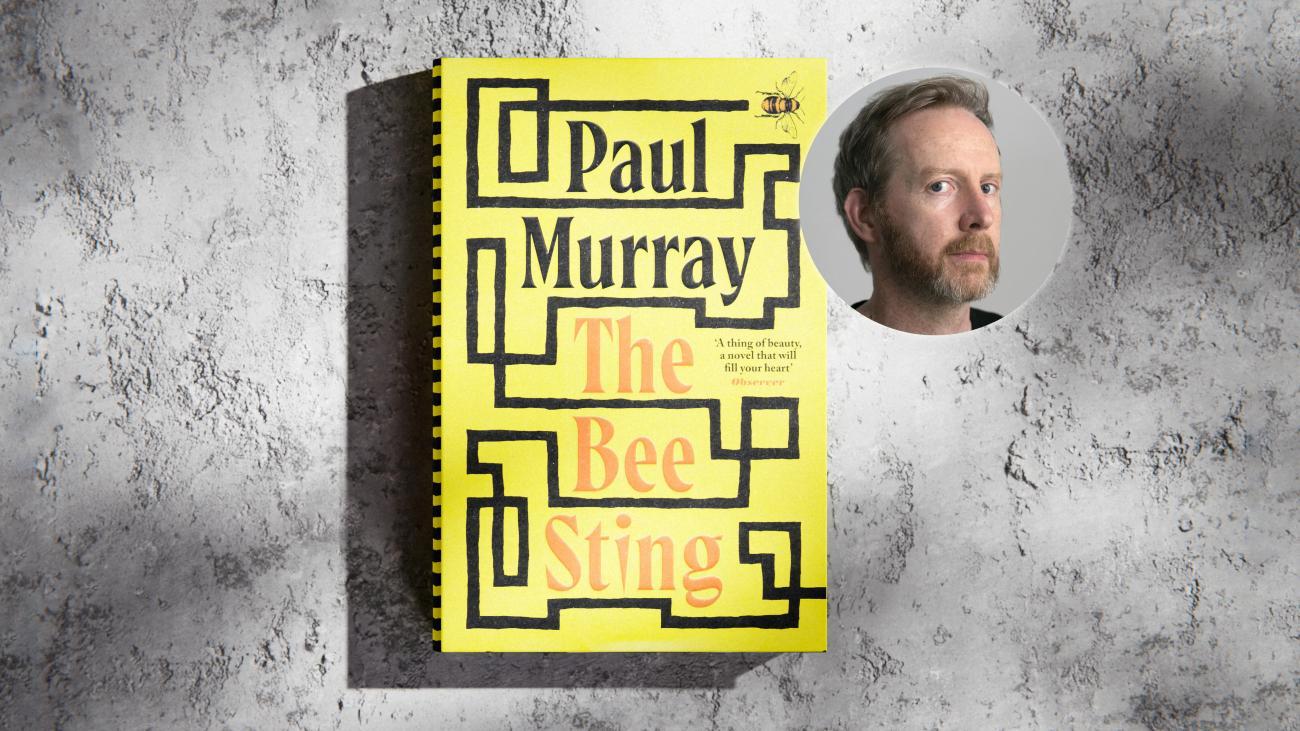

Trinity alum Paul Murray rejects this scripted reality. For the author, recently shortlisted for the Booker Prize, following hollow cues can only lead to disaster as portrayed by his characters from The Bee Sting, Cass, and her father Dickie, Trinity students who succumb to conformity. To an extent, their ruinous experiences encapsulate our social pressures. Students comprise a painfully self-conscious generation; we know (especially due to online discourse) that specific roles are more desirable than others. That said, Trinity students are still young aspirants. Searching for our authentic selves, we haven’t memorised our lines nor let our masks supplant our faces. Maybe we can still escape this socially performative theatre (maybe).

Youth runs on contradictions like America runs on Dunkin, with conformity meaning nothing and everything for its capacity to define our later lives. Murray recognises retaining your autonomy is hard in this atmosphere. “I guess [I find] teenage years quite operatic. When you get older, you learn to tamp down your emotions to a certain degree and assimilate and pretend you’re like everyone else.” According to Murray, these moments make for good fiction because characters are not yet trapped in the script of marriage, career, and family that define adult life. We can conceivably “break free” from our typecast roles.

“Kierkegaard wrangled with how to find meaning in life, proving you do not need to wear Doc Martens to possess a tortured soul”

This dilemma does not just apply to the sullen girls and boys of Ireland. Within Fear and Trembling, Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard wrangled with how to find meaning in life, proving you do not need to wear Doc Martens to possess a tortured soul. He concluded the importance of finding the “one thing in your life that you truly believe in and you live your life according [to the connection]”. This ethicality or higher immediate purpose is intensely purposeful, whether it is loving a girl or sacrificing your son on the top of the mountain. We are thoroughly unlikely to find it by going to parties or seducing women in a nightclub or following the morals espoused by mass media culture. Kierkegaard sounds like he would be very fun at parties. However, Murray says he has a point. There is no one kind of ethicality contrary to the material fictions and virtuous signalling we counter on a day-to-day basis. We all have our individual purposes that we may encounter at any time. Maybe we will find it within a particular book.

Certainly, Murray found himself frustrated with social performativity in college. He found his solace in literature, citing multiple discoveries: “I discovered Thomas Pynchon while I was at Trinity – his novel Gravity’s Rainbow was a major inspiration and also his totally and insanely uncompromising attitude to art, like never doing interviews, being photographed.” He admits: “I used to read Vineland in the stacks when I was supposed to be studying.”

“I was just looking around me and thinking, what is the point of any of this stuff?”

He notes that his Senior Fresh year was pivotal to his development. He remembers reading the modernist poets, “particularly William Carlos Williams, especially The Red Wheelbarrow”, admitting that while he didn’t understand them, trying to make sense of the texts signified a “breakthrough”. He cites Donna Tartt’s The Secret History and Lorrie Moore’s Self Help as akin to “fireworks displays”. Murray still found himself annoyed with the norms observed. He recalls: “I was just looking around me and thinking, what is the point of any of this stuff?”

Murray still asks the same questions but says most adults stop wanting answers. Instead, we learn to veil ourselves in illusions: “They remain valid, but you stop saying them because you don’t want to rock the boat as much.” Teenage characters enable Murray to critique the world and embrace the possibilities for change our generation propels upstream.

Like it or not, we may find ourselves in the same boat as our parents. The Bee Sting is predicated on the tensions between generations, or Cass and Dickie as they share a tumultuous relationship. During the car ride moving Cass to college, the pair experience a breakdown in communication, with Cass barely speaking to her father. Murray says the teenage characters feel “frustrated and constricted by this world presented to them” and see their parents as “monolithic lawgivers who don’t give emotional authenticity”. The process of acting out contrasts itself with the stable institution of parenthood. Acting out can be seen as a way of escaping this institution’s nonsensical rules, venturing away in hopes of finding an authentic place without them.

Still, we feel compelled to uphold these norms. College is not a fairytale but a place where a group of highly pretentious, anxious, and neurotic individuals sit around and judge each other for a few years (or at least that’s the Arts block). Murray says Cass doesn’t find her people until late in the book, which disorients her because “her whole trajectory is being like, I’ve got to get out of this town to get to this magical place where everyone’s just going to get me, and I’m going to get them, and we’re going to like each other, and it’ll all be simpler”.

“You’ve got to find out who you are, and no one else will do that for you”

“And that’s the absolute opposite of what Trinity is like and what the world is. You’ve got to find out who you are, and no one else will do that for you. Unless and until you do find out who you are, you’re constantly going to be subjected to just the flux and illusions of the world around you. It’s never going to be easy.” As many of us fixate on the next life stage, this insight is reassuring and terrible. We might all be in the same boat, but that doesn’t mean it is a pleasant experience; knowing that another turbulent ship will set sail after we disembark from college evokes emotion sickness.

In time, all our youthful illusions seem posed to have their Titanic moment. Murray explains that when we are young, we are romantic about people, whether it is the notion of one person we will fall in love with or just that “you’ll be absorbed into this utopian state of happiness”. Then comes the iceberg of reality. It certainly hits Cass hard. “When you get to college, you find that everyone’s not automatically authentic or honest … Cass thinks her parents are empty people, but at least there’s stability, [at Trinity] she’s obsessed with her friend Elaine [who is] always changing herself to try and fit whatever way she thinks, whatever way she thinks people want her to be.” This inauthenticity rings true in a college celebrated for debate, the model for artificial expression masquerading as genuine sentiment.

Still, even though the truth may sink into our consciousness as we age, that doesn’t mean that wreck is any easier to cope with. Adults still flail around in the water, and there is seldom a conveniently located door. Murray says that he realises the delineation between teenagers and adults is superficial: “under the surface … You’re still trying to figure stuff out, but you learn to cover it up better. So you stop making these massive, embarrassing platforms that you do when you’re a teenager, but also you stopped doing interesting things for the same reason, or you could stop doing interesting things because you have a certain kind of structure to your life now, a certain persona that people buy. Oh my god, I’m the manager of the Bank of Ireland, or whatever it might be.”

Do we have to embrace falsehood to achieve social acceptance? Murray lets Cass grapple with this question through her obsession with Elaine, who is “the poster girl for what’s good now because she switches herself around to fit Trinity’s idea of a good person as she sees it”. Cass finds herself as a sidekick to the superficial Elaine, who embraces largely performative politics, discarding and picking up their friendship as she pleases. Although such relationships are tempting, their friendship displays how casting ourselves into performative roles yields minor and dissatisfactory parts.

“Even when you know these bright city lights are artificial, it is hard to let them pass”

Returning to Kierkegaard, Murray also cites Fear and Trembling’s Knights of Infinite Resignation, who fall in love with a princess. This love is their central purpose in life, but they ultimately recognise it is impossible to be with the princess in the finite world. Yet they struggle to find spiritual meaning when resigned to a life without their purpose of love. Likewise, Murray believes that once you find the drive within yourself, “you’ll have to decide whether you want to live by those lights or whether you’re just going to keep going”. Even when you know these bright city lights are artificial, it is hard to let them pass.

Granted, Kierkegaard didn’t have to contend with the Internet. I can picture him sadly liking all the posts in his former fiancee’s Instagram feed. Murray acknowledges that although stress and anxiety have always been present, “social media has amplified that a thousand times”. He says that when he was in college, “people were trying on personas, and that led to a lot of pretty dickish behaviour” but still promoted a free atmosphere, whereas nowadays, “everything is critiqued and ranked … it’s so hard how you could find out who you are if you’re constantly trying to develop your brand at the same time.”

“I mean, you’re trying to make people like you at the best of times, but suddenly you’re trying to make all of the internet like you, and everybody’s got an opinion on your song or your moustache or your breakfast, and it sounds so claustrophobic and hard and just fucking heartbreaking.” This toxic discourse is to the active detriment of creatives. Murray recalls the story of a colleague, who received a three-star review citing “while he [the reviewer] admired her work, it didn’t blow his mind like Emily Dickinson did.” Writers critique themselves already; the internet creates an additional devil – or worse, an obnoxious man – on their shoulder.

Murray says that keeping yourself hidden is still our active reality. The character Dickie grew up with the homophobia of Catholic Ireland, and although there’s more acceptance, the nature of exclusion has also evolved. Cass and Elaine aren’t straight, but Cass feels she does not “tick the same boxes” as Elaine and “whatever she’s doing is wrong. So she’s going to the gay bar, but she still thinks she’s dressed wrong, and she’s not this enough, she’s not that enough. And it’s just that all these new rules appear.”

Social norms may have shifted, but we continue to find new ways to not fit in with the status quo. “I don’t think we should all be living in vans and drinking kombucha and smoking weed and playing the ukulele all day, but what happens in societies is that one way of living is replaced by another way of living. But both times, there’s just one way. It turns out there’s just one way. And if you don’t fit into these special interest groups, then it can be just as difficult as the previous way … you’re just as isolated as you were in your little small town where nobody was different.”

Can literature provide solace from these social boundaries? Most of us find comfort in literature, knowing we are not alone in our flaws. Cass finds solace from sexual repression by writing poetry. Murray says this mimetic search is common to young people as we aim to define ourselves. “You’re looking for people who have lived authentically or feel they represent your experience, and then you try to copy them.” If your friend groups feel “oppressive” or “you feel alone” in our digital age, art symbolises the opposite. Interestingly, the internal messaging of a book often provides more genuine human interaction than social media’s externally focused superficiality.

“When you read a book that you love… that’s uplifting, and it gives you the courage to keep trying to be yourself”

Murray recognises the importance of young people identifying themselves in literature: “When you read a book that you love, or you listen to a piece of music that you love, and it seems to authentically just kind of resonate with you … that’s uplifting, and it gives you the courage to keep trying to be yourself.”

When he was in Trinity, Murray was “really attracted to writers who didn’t care about money or success in conventional terms”. He still finds this concept incredibly appealing, “that you could do what you love and do it no matter what was a thing you could do … It was just a door that opened and saved my life.”

We can live our authentic lives through the medium of art. Granted, the social theatre permeates everything. Writers face pressure to market themselves and follow the trajectories of writers they admire. “If you’re an artist, you have to find your own voice. If you get the approval early on from gatekeepers, it can encourage you, but it can also arrest you at an early stage that you would have otherwise moved past … you look brilliant, but that’s no template of how to be an artist.”

Life imitates artifice already. Closing the curtains on the fair, Murray suggests we should be devising works fulfilled by our higher immediate purpose instead of what we think people care about. If we seek the truth about ourselves, we should embrace the art of living as we please. Whether you feel called to become a writer or a Bank of Ireland manager, heed it with confidence and your selfhood will shine – as a wise elder (me, a senior fresh) once said, who gives a damn about the spotlight.