How to unlock the poetics of space: first, commence the battle between upstairs and downstairs. Upon entering the GMB, I was confronted with a host of nerds anxiously clutching wine glasses. Realising I had made an error, I naturally ran away. Upon running up the stairs of the GMB, I was confronted with a host of nerds anxiously clutching wine glasses and poetry pamphlets. Ah yes, I thought, I’ve found my people.

The Hanok Review is a Korean literary journal dedicated to rendering Korean poetry accessible to a broader audience through translation. Led by Editor-in-Chief Nicole Hur, the November 15 launch party was dedicated to their second issue. Opening the event after attendees had downed wine (and the bottle opener mysteriously vanished), Hur explained that the collection is dedicated to the father of Poetry Editor Jess Kim, who recently passed away.

“We noticed the generational ties hanging on the walls of the collection, which imbued us with the sensation of being displaced back to another time”

Although we stayed still, nevertheless we found ourselves moved. Moving, moved already by Hur’s words into the insides of a space with which we were unfamiliar, namely the titular structure. A hanok is a traditional Korean house. Passing on our way through the opening poem ‘Departures’ by Inkyoo Lee, we noticed the generational ties hanging on the walls of the collection, which imbued the audience with the sensation of being displaced back to another time. Unified in silence, we listened as Hur lifted us away from the tired confines of our bodies and welcomed us through an open door.

Underneath this imagined arch, Hur explained the translation process: “The lead translators do the bulk of creating drafts [and are] in charge of how the final form looks like.” Leading us down the hallways: “As a team we will comment in detail how things could be altered or changed to better accommodate the original piece.” While the Review receives and encourages translated submissions, most are accomplished by their team of young translators around the world. Anticipating the spread of their words, we settled into our seats.

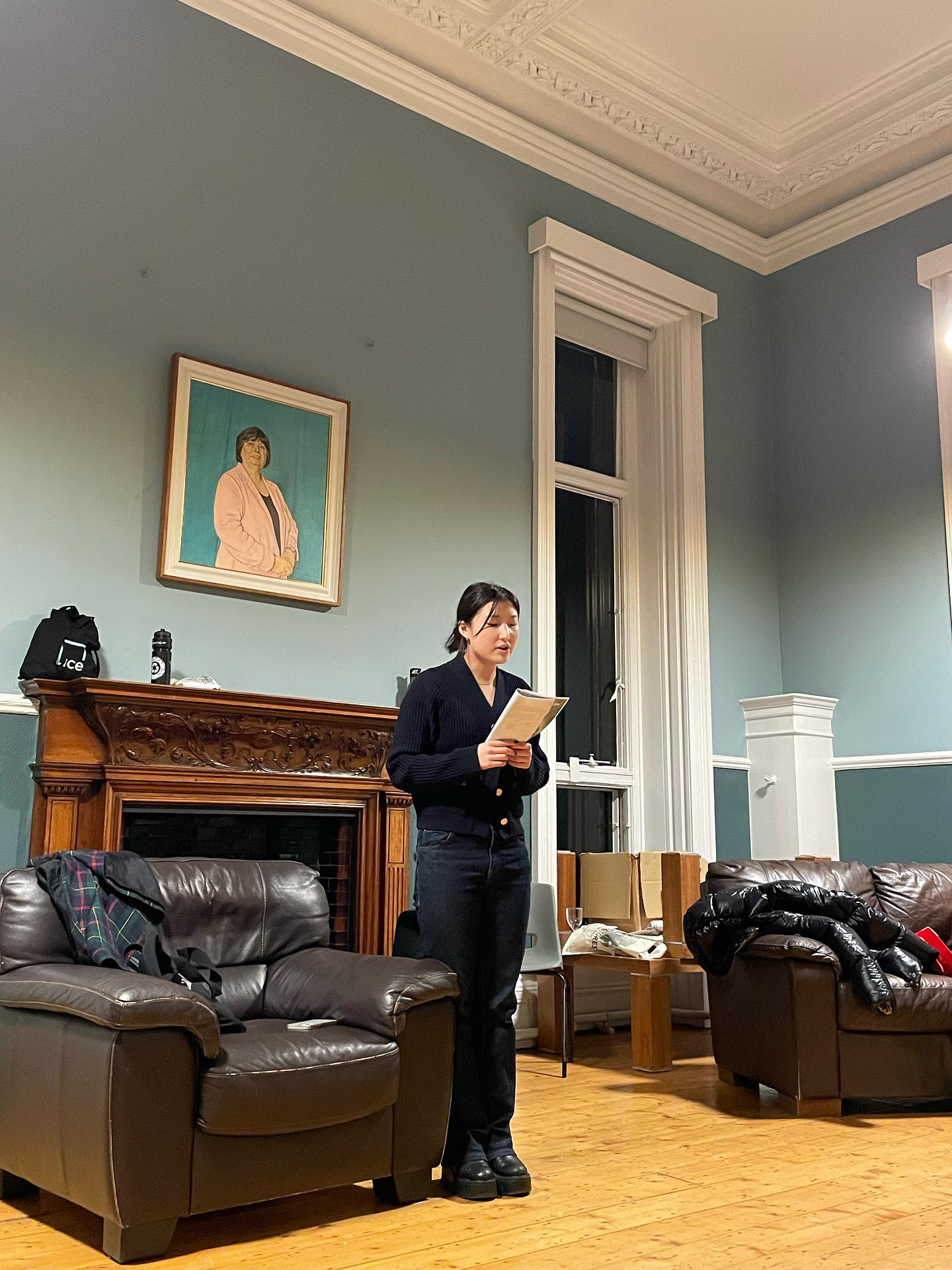

Over unembellished furnishings, the translated poems Hur laid out were all the more striking for their minimalist presentation. In other words, they managed to articulate the flow of how we actually think. Most of us don’t articulate our experiences in, say, the heightened terms of an epic, because even during the worst heartbreaks we are not Achilles speaking to Patroclus or Héloïse to Abelard. Still, we feel deeply. The poems managed to encapsulate these emotional heights in a relatable frame. A traffic light, a keycode, even ordinary food you find around the household. Physically, these are objects of diminutive stature. In personal terms, they expand to fill us with the hunger for a moment forever lost.

“We can all understand the pain that accompanies losing someone close to you and the impossibility of articulating what they meant”

Savouring this moment’s recreation, we inhaled how the tofu “cools / calmly, as if it has already experienced death several times over” as “I touch the tofu / I’m touching the final moments of a time that no longer exists, a warmth that cannot be conveyed” from Archana Madhavan’s translation. We may not know the particularities of poet Yoo Byung Lock’s life. Irish people may not understand tofu. Still, we can all understand the pain that accompanies losing someone close to you and the impossibility of articulating what they meant. As complex individuals, we transcend definition, shifting to suit different social structures and relationships. The delight of this experience is to be surprised when someone defies your limited perception of them, or even when you comprehend it, to observe the changes, variations, renovations, if you will, to the mounting tower heaped with small observations and things you love about them. But then, of course, it falls. And you can paint all the pictures or write all the poems you want, but nothing will ever match the image seared into your brain.

Readers, however rapt, will never be able to comprehend what this tower was like. This is to be expected; its foundations are far too complex to reconstruct in their entirety. But anyone can understand a small fragment, like a food or the ocean. Possibly because this was part of their own tower. From this support, you may find the basis not for what you made (never) but for something new. Eventually, you might have something to live in again.

“Certain words in Korean are laden with meaning that doesn’t necessarily translate to English”

Through serving these small moments, creative acts can prove cathartic. More specifically, the Hanok Review’s translating is special for conveying both the universality and particularities in Korean cultural life. Tofu, for instance, is a Korean household staple but that might not be the same in your home. Certain words in Korean, like 엄마 and 아빠, referring to mother and father, are laden with meaning that doesn’t necessarily translate to English. Even something like a passcode, which we may think we understand, carries different weight in Korea. “You would enter the house with a passcode, so it’s kind of regarding that,” Hur said after reading the poem Passcode, written by Moon Hyun-sik and translated by Sal Kang. Speaking about the boxes that accompany the text, she explains: “Each box signals the digits of the passcode, and when you put in a passcode everyone has a different beat of how they put it in.”

“It’s a secret knock knock, and you know by the rhythm of the knocking that is… perhaps suggestive of a death because the sound has faded away.” Knocking on the door, the poet opens up about their grief while refusing to divulge the code itself. Likewise, the global team of translators aim to project every poem’s themes without peeling away the uniqueness of Korean culture itself. Moreover, setting these protective barriers may encourage connection, since readers unfamiliar with Korean words and themes must learn about them in order to relate the poem’s implications to their own lives.

That’s why in several instances, the Review’s translators refuse to conform to English language conventions and opt instead to transliterate (when you angliciphonise or spell out a different word into English) words, such as 엄마 to ‘eomma’ or ‘mother’ in Melanie Hyo-In Han’s poem about having a mother with cancer. Due to an increased interest in Korean culture due to the ‘trendiness’ of phenomenons like Parasite and Squid Game, often translators feel compelled to make poetry as accessible as possible. While increasing accessibility remains the priority of the Review, Hur is determined to avoid the Western design outlook’s confines.“You lose a lot in translation,” she said in a panel after the reading with DU Languages Soc Chair Michelle Chan Schmidt, Literary Society OCM Nicole Battu and K-Soc Chair Yunkyung Kwak. “With the ones we’ve decided to transliterate, we found when you put it in English, often [the perfectly clean translation] doesn’t encapsulate the same loving or endearing message of a certain word. We want to transliterate, so non-transliterated words would not encapsulate the same meaning”.

“There’s this idea that a translation should be perfectly clean, but… you are losing a lot of the focus from the thoughts in the original language”

Hur clarified that direct translation is sometimes necessary, especially for “words that aren’t as common as ‘mom’ and ‘dad’, we tried our best to translate it in English”. That said, when taken too far, the other panel members agreed the practice can disrupt the poem’s structural integrity. Ahn Do-hyun’s original poem The thing that seeps contains a phrase that translates directly to “crying crying”. Hur explained that the original word in Korean “has the cathartic release of sobbing which translator Ainee Jong aimed to replicate through the translation ‘sobbing sopping’”. As Hur said: “There’s this idea that a translation should be perfectly clean, but I think if you’re doing that, you are losing a lot of the focus from the thoughts in the original language. Since a lot of our staff is bilingual, we understand the importance of balancing both cultures.”

Despite noting the difficulties inherent to the process, Hur ultimately finds the beauty in its imperfections. She believes that “in that sense it’s pretty exciting”, since increased translation of Korean poetry can help contemporary writers in Korea find globalised audiences and evade reductive standards set by the publishing industry.

Ultimately, translation is fundamentally creative. Poems may not conform to the exact plans laid out by the poet, but Hur stated that this is not necessarily negative when the translator can back up their artistic choices. She said: “I wish there would be more taking the reins and risk taking [within translation]… I feel like if someone were to translate my work I would be like, ‘Go crazy!’… You can create so much work when there is no pressure. Why are we so stuck to rules? I think that’s only going to limit us.”

“I should say: the house shelters day-dreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace”

Thriving on the contradictions, the tensions within intergenerational discourse, the spaces between the grid lines, The Hanok Review’s launch reaffirmed the resonance of Korean poetry, maintained thanks to the cultural sensitivity of a global team. Author of The Poetics of Space Gaston Bachelard once said: “I should say: the house shelters day-dreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” The Hanok Review may not be a place for peaceful dreaming, but in all fairness who has time for peaceful dreaming these days? Instead: losing, sobbing, sopping and embracing our new selves while imagining the past, we welcome glimpses into the windows and hearths expressed in poems. For a moment we can come in from the cold.