Ireland’s stained-glass windows are enjoying renewed appreciation in this wintry gloom. With a string of recent acquisitions and exhibitions in heritage institutions nationwide, interest in stained glass is alive and well.

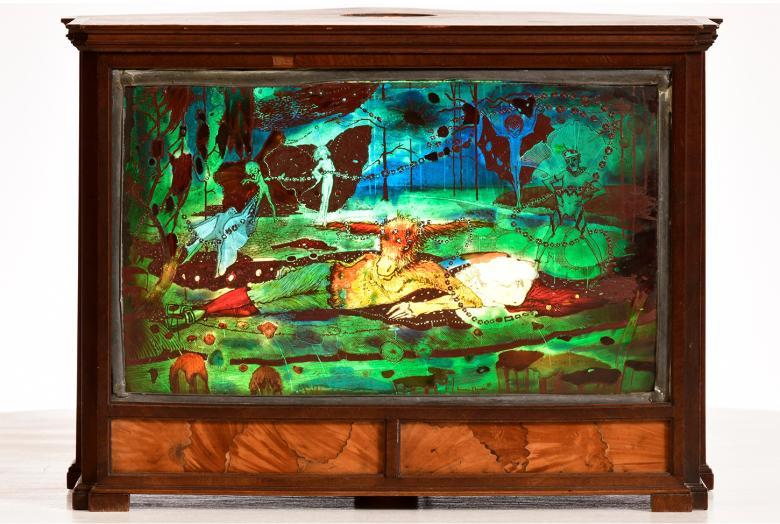

Where did this begin? The National Gallery of Ireland (NGI) acquired a rare Harry Clarke glass panel in late 2023, a murky and mesmeric depiction of “Titania and Bottom”. It is Clarke’s only known rendering of a Shakespearean scene. The window is now on display in Room 20 of the National Gallery.

Recent acquisitions are not limited to Dublin, either. The Crawford Art Gallery has purchased a colour plate of “The Colloquy of Monos and Una” by Clarke, one of a 1923 set of illustrations for Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination. Although not a glasswork, this shows that Clarke’s art is still being snapped up at auction regardless. These acquisitions by heritage institutions allow the artworks to remain accessible to the public, as opposed to being housed in private collections.

“An Túr Gloine stained glass studio was founded in 1903, and this will be the first exhibition of its extensive legacy.”

In the works now in the National Gallery exhibition, “An Túr Gloine: Artists and the Collective”, the works of Wilhelmina Geddes, Micheal Healy, Catherine O’Brien, Alfred E. Child, Hubert McGoldrick and Evie Hone will be on show. An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass) stained glass studio was founded in 1903, and this will be the first exhibition of its extensive legacy. It opens with free admission from 30 March 2024 until 12 January 2025. Curated by Marie Lynch of the Centre for the Study of Irish Art, it is sure to bring renewed consideration of the place of glassworks in Ireland’s artistic heritage. At the other end of the country, the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork runs an annual Harry Clarke exhibition, although this year it will also feature the additional colour plate.

One central figures in stained glass is Dublin’s own Harry Patrick Clarke RHA. Clarke inherited his father’s studio and produced some of the most recognizable stained-glass windows the world has seen. He died of Tuberculosis in 1931, and management of the studios passed to his wife Margaret Clarke née Crilley RHA. She was a talented painter in her own right, with a retrospective exhibition at the NGI as recently as 2017.

Harry Clarke’s remains are currently in an unmarked common grave in Switzerland. Given the sustained interest in Clarke, it remains to be seen whether or not he will stay there. Among his belongings here in Dublin are complete windows, watercolour illustrations, and personal effects at the National Library including an eye patch and satchel. Allegedly, an unfortunate insect lies squashed between the pages of one of Clarke’s diaries. These are all accessible to the public through libraries and archives. Dublin has an especially rich material heritage available to researchers, practising artists and students. It would be unfair to highlight Clarke above his contemporaries, though arguably the national psyche responds with fervour to his humorous, gothic style. Like Clarke, the collected effects, illustrations and correspondence of many artists are housed in Dublin, often spread between heritage institutions.

“Micheal Healy mastered techniques such as aciding and placing two pieces of glass together.”

Of late, the window of Hodges Figgis displayed copies of a new hardcover tome by David Caron. The book is “Michael Healy 1873- 1941: An Túr Gloine’s stained glass pioneer”. Micheal Healy was a talented and dedicated artist from humble beginnings in a Dublin tenement. He mastered techniques such as aciding and placing two pieces of glass together. These are the techniques for which Harry Clarke is now lauded in galleries, not to forgo mentioning fellow artist Evie Hone (1894-1955) who was a crucial figure in bringing modern art to Ireland.

The association of stained glass works with churches and cathedrals is natural. That said, secular pieces drawing from literature and folklore prove just as compelling. Some exquisite contemporary stained glass have been produced by Johnny and Roísín Murphy, and Peter Young (b.1962). I should admit to a degree of personal bias in choosing which artists to mention here!

“Considering these artworks, I would not be surprised if Irish stained glass gleams another hundred years from now as one of our most iconic and moving art forms.”

All this is to say that Dublin has not ended its love-affair with stained glass. By 2026, a new Harry Clarke Museum of Irish Stained Glass is proposed to be open in what used to be the Dublin Writers Museum. Perhaps we might see Harry Clarke’s Geneva window visit the city from its current location in Florida, but the chances are low, given the fragility of glass windows. With these artworks soon to be lit up and a steady flow of high-quality publications, I would not be surprised if Irish stained glass gleams another hundred years from now as one of our most iconic and moving art forms.